Content warning: This article deals with racial trauma, depression, and anxiety

Madge Yang’s multi-media collages depict nuances of the Asian American experience

It’s a balmy day, and Madge Yang is in her New York apartment, looking relaxed and in her element sitting by a bright window. Her smile flashes mid-thought, and her voice, slightly raspy and full of feeling, is candid. We’re talking on screen and are having a great conversation, though there’s no way to note her gait or a quaint interaction with someone at a table nearby. It’s okay. As it goes with most Zoom interviews these days, we can actually delve into what motivates her without any distractions.

During the initial moments of our conversation, Madge brings up coronavirus, remarking how impossible it is to talk about the politics of it without considering the past. “The wars, relationships, and trades made decades ago affect discussions about how the virus spread, how it’s treated, how vaccines are being manufactured and sold and administered,” she says. Of course, she’s right. The political climate is fueling hate crimes against Asian Americans, touching every person in the community. Along with it, we’re experiencing yet another wave of the Delta variant and the fall, school year and all, is again not shaping up the way we thought it would.

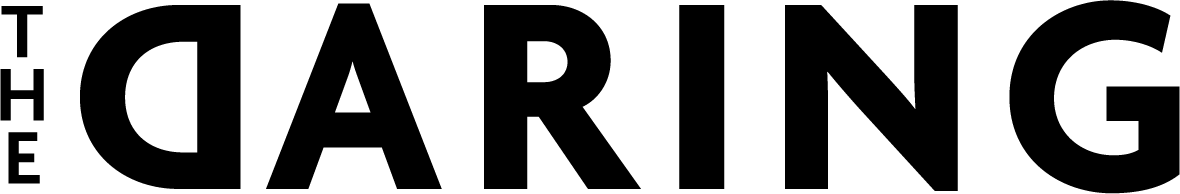

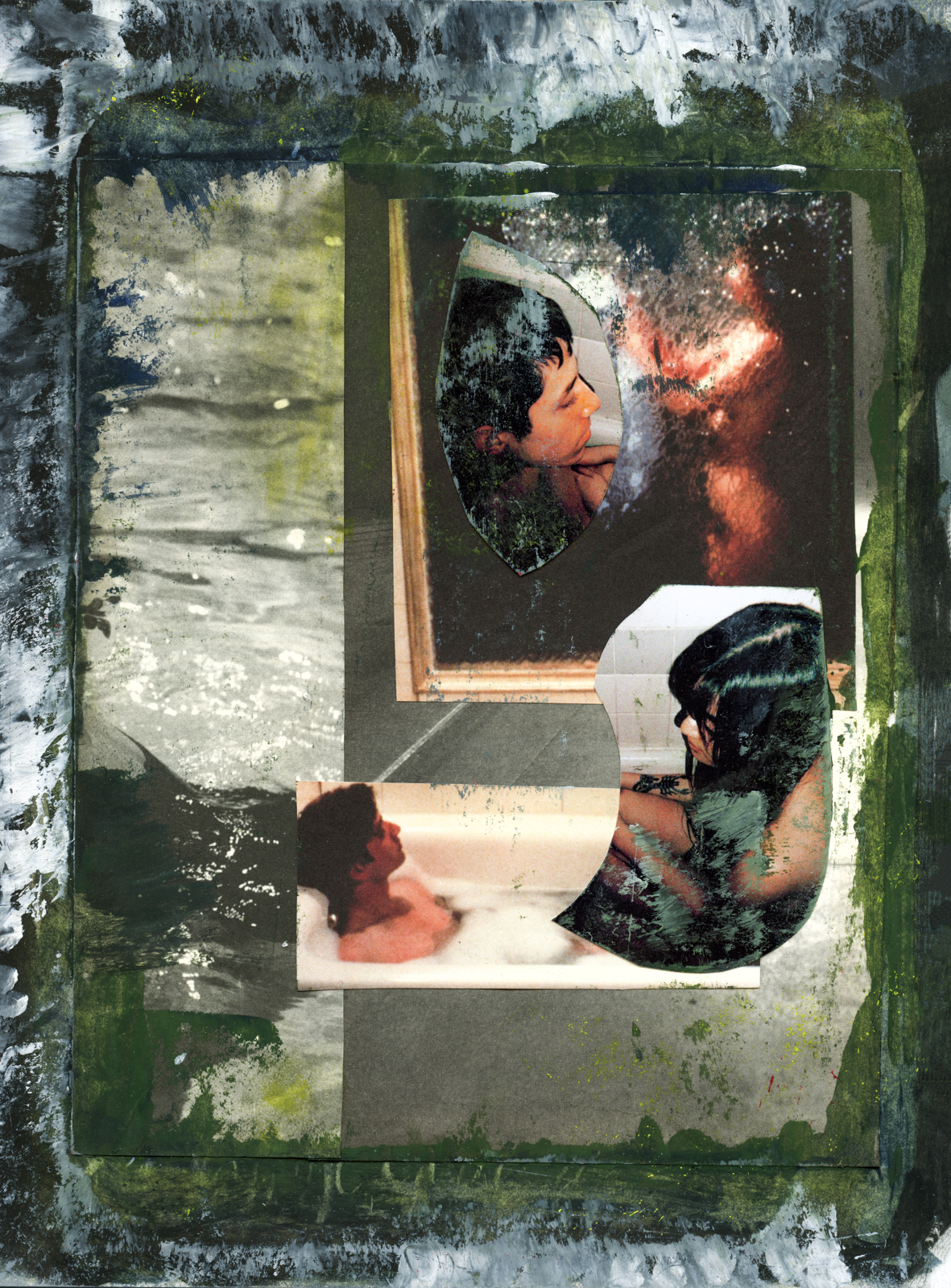

With all that’s happening, Madge is figuring out that balance of knowing when to create and when to rest. One thing she’s definitely doing is putting her whole heart into artwork, centering so much of it around identity and mental health. With the dexterity of a bohemian artisan, she turns the tensions she feels into visual poetry to help ease them. Her works are unsettling and that’s exactly the point.

Madge works in a saturated palette, using mixed media — including fragments of vintage magazines, photography, lettering, paint, and embroidery — to create visual narratives that dip into sci-fi. She speaks of “creating a horrible nightmare on paper” to release herself from it. It’s all deeply personal art that takes up power and pain in manners that are expansive, uninhibited, and fiercely introspective.

Madge was born in Flushing, Queens and grew up there and in Vancouver. She started figure drawing at eight years old, then got into photography by publishing Jeune Fille, a zine “full of vernacular feminist-aligned images of youth” in her area. She stretched her creative legs making portraits and lighting shoots in a photography studio she set up in her basement. It was an act of rebellion, to love art and to pursue it across the continent. Her practice has brought her to School of Visual Arts, where she’s majoring in Photography and Video.

The Daring: What’s your first vivid memory?

Madge Yang: I love this question. I remember being a young girl, in between my parents, and they were swinging me by the arms, maybe down the street or in a park. It was warm…a spring or summer day.

See, the mystery about memory is how much of it do we recall, and how much of it do we fabricate based on the evidence we have? So right now, I’m thinking, “Oh, well, I was born in New York, so it was probably loud as shit in that moment.” Because it’s loud everywhere here. But who knows?

TD: So true, memory gets foggy. You’ve talked about feeling a deep need to record everything, which gives your work a diaristic quality. How do you think journaling relates to the immigrant experience?

MY: Yeah, I journal and it’s therapeutic, poignant even, because I’m recording memories and thoughts. But at the same time, journaling is evidence that you’re a little lonely. You’re essentially recording your need for introspection and clarity in that moment — and you’re by yourself. There’s something beautiful and sad about that at the same time.

When we’re talking about being a refugee or an immigrant, journaling often comes from loneliness. It comes from being an outsider in a vastly new place, even though you’re also excited to be there. So you’re recording all the new experiences you’re having. It’s a little cynical to say it’s sad, but there’s a bittersweetness to it, which is lovely.

TD: Why do you think you grew up to make art about cultural divides?

MY: My work is about being Asian American, the differentiation between East and West, and living in a political climate post-cold war. A lot of tension comes with embodying these divergent parts of the world. That cultural disconnect results in disconnect within the household, and for most of my childhood and teenage years, I felt extremely isolated from my family. At the same time, I felt extremely isolated by my peers.

I didn’t feel connected to my heritage, but I also did not feel connected to my community in North America, in Canada. Even though Vancouver isn’t a small town, it feels like it. Any sense of individuality was a rebellion against the norm. I spent most of my time working on creative projects and making money to leave.

TD: What was it like to move from Vancouver to New York?

MY: At the moment it was terrifying…and exciting! When they were my age, my parents moved out of Yantai, Shandong Province, and came to Queens with no money. They didn’t speak the language, and they had to make all their money themselves.

So I felt as if I was pursuing my parents’ pilgrimage and replicating this coming-of-age moment. I have the safety and comfort of at least being from North America. So it’s not the same, but we’re mirroring one another’s life experiences in our twenties. My parents were sad I moved away, but they ultimately supported it because leaving their hometown and traveling the world is one of the greatest things they’ve ever done. They wanted that for me. It was really exciting, yeah. And hilarious too.

TD: What brought you to making collages?

MY: I saw Frida Kahlo’s journal, and I became obsessed. She would write and paint and sketch in it. And I loved that because even though I’m a visual artist, I also write prose. So, I started assembling cutouts in my sketchbook, but I never made compositions intending to have them look nice. I was playing with images and, in the same way journaling is therapeutic, I was collaging to calm myself down and to reconnect with my mind.

I’ve struggled with social anxiety for most of my life, and a large part of photography involves people. In college, I went through this existential crisis and felt this huge weight on my shoulders of being an adult, of being alone. The anxiety heightened to where I couldn’t interact with people anymore. So, I had no motivation to make portraits because that had come from a desire to connect with people. I started printing images of people I’d hung out with, and I worked with those. So, I was still creating compositions, but in a way that helped me cope with a fear of people. Collaging was calming, and I got better and better at it.

TD: Your pieces have a craft-making quality…where’s it coming from?

MY: Many of my processes are based on craft-making because it comes primarily from women, who historically don’t have the same artistic notoriety as men. Anni Albers, the textile artist, is a great inspiration to my practice. My grandmother taught me to crochet and knit, and I’ve done that since I was young. I am obsessed with these tactile practices, which feel restorative for me. I’m less focused on creating beautiful images and more focused on crafting useful tools for myself and others.

And I depict ideas in a fantastical way, but I ground them with literal imagery. I used neurological scans in a project about mental health. What is more literal in talking about mental health than actual brain scans? I researched scans, and I studied their shapes and shades. I played around with them, and this composition happened with a large X in red thread embroidered on it. The thread is a reference to artists working in textiles, like Anni Albers.

TD: And what attributes do you look for in archival images?

MY: I flip through stuff very quickly. Imagery calls to me, and I feel it when it enriches a theme I’m exploring. I tend to consider the subject before I look for images. And when other images strike me, I note how they could be used in compositions later on.

I have an organizational system where I sort out pieces of paper by size — large, medium, small. I have Ziploc bags filled with cut letters, also organized by size. And then, I also organize cut-outs by subject matter.

I have a huge archive of magazines I’ve collected, some from friends and some from garbage piles. Beautiful, old Life magazines with war imagery. Porn magazines from the seventies. And I look through it all. And for example, if there’s a spread of an Asian woman, and it’s from the seventies, of course, it will say “jungle lady” or something really weird and uncomfortable. But pornography has never respected cultures or women so, who’s surprised? But when I see something like that, it’s wow! It’s great for the stories I want to tell, and I rip out part of the page.

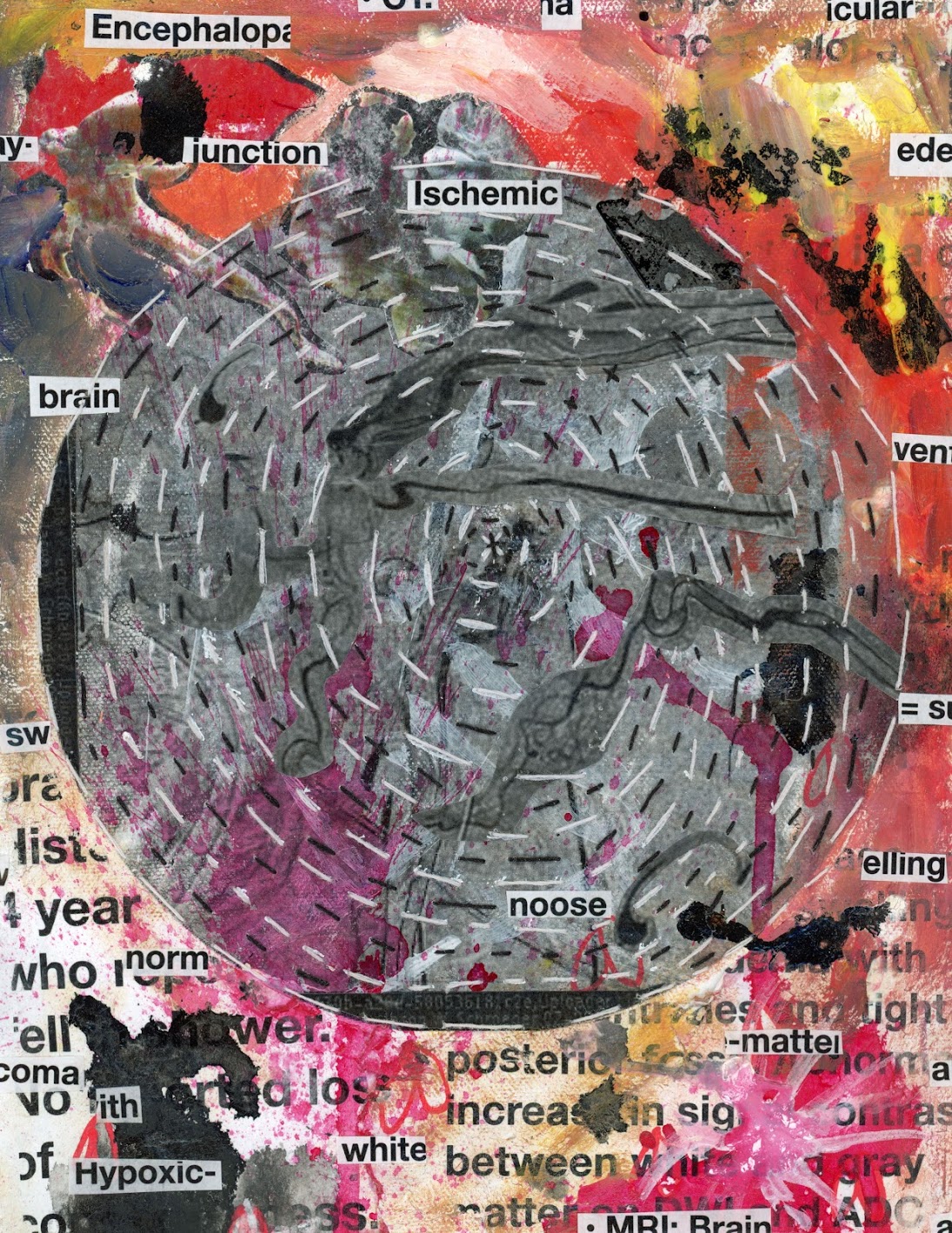

TD: You use Mandarin characters in some works. How do you think about their role?

MY: Yeah, Mandarin is my native tongue. Before I went to preschool and kindergarten, my parents spoke Mandarin with me. Even now, I speak Mandarin, but not as well.

I use them as a calling, just in case anyone who’s a Mandarin speaker is looking at my work, I can say to them that we are the same. I want to make sure my work ties to my heritage. So I use the characters to tie modern photographic clippings from American magazines to the traditionalism of Mandarin and my culture. Tying these different languages — photography, English, Mandarin — to create pieces that can speak to as many as possible is something I find important.

I like the way Mandarin characters look. I like that they’re symbols and words. It’s different from the English Roman alphabet in that the characters themselves are paintings. They are depictions of scenes.

TD: What do you want to say to the wider world about the Asian American diaspora experience?

The migration of Asians towards the West is noticed but not considered through historical context. That’s what I aim to shine the light on.

The Asian American experience varies depending on every individual’s story, ethnic heritage, class, where they lived, and their upbringing. The continuous tension between the West and Asia, from Hiroshima to the so-called “Wuhan Virus,” has resulted in a population of immigrants who were born, raised, and have accepted the paradoxical cultural identity that comes with being Asian American.

Sociologically, the Asian American identity is so incredibly new, having only come into existence post-WWII. It’s not that Asian American people haven’t existed for decades…we can refer back to Japanese internment camps in northern California in the 1940s and the wave of American ex-pats in the Philippines since the early 1900s. Unfortunately, similarly to most ethnic groups who found a home in America, the story of Asian Americans and their settlement here has to do with seeking refuge out of consequences of war, and as a result of globalization and Western Imperialism.

I am dissecting the nuanced and often hideous elements of being an Asian American living within the culture war between East and West, and I’m creating a theatre out of this violence.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Madge Yang (b. 2000) is a New York-based female artist working with elements of photography, painting, and collage to create compositions regarding themes of identity, mental illness, and generational trauma in regards to being Asian American. Madge Yang is currently studying Photography and Video at School of Visual Arts, and divides her time between New York and Vancouver, Canada. Visit madgeyang.com.