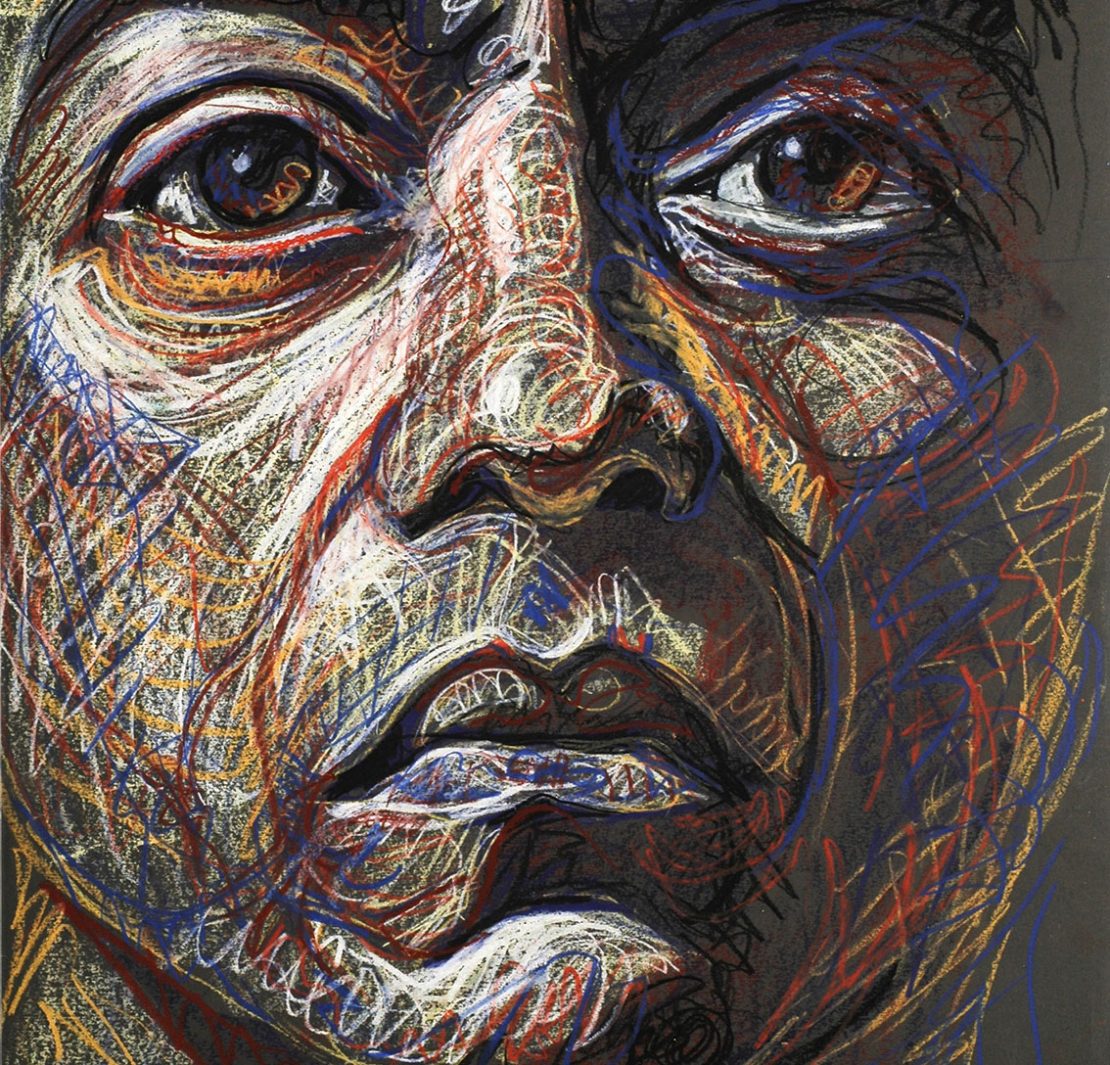

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

Fred Hatt’s Triumphant Portraits Bring a Fresh Perspective on the Human Body

“We can only experience the world in the form of a body that is inherently temporary”: The artist talks about the human form, drawing people, and why he takes such a multidisciplinary approach.

I met Fred Hatt in 2020 at MoMA, where he is a film projectionist. The pandemic had already swiped across the world and come to a brief pause, and people began to feel hopeful again. A mutual friend, Rachel Wyman, introduced us as we ventured out to collaborate on an art project revolving around a poem I wrote. She was the movement artist, and Fred agreed to be the videographer and producer.

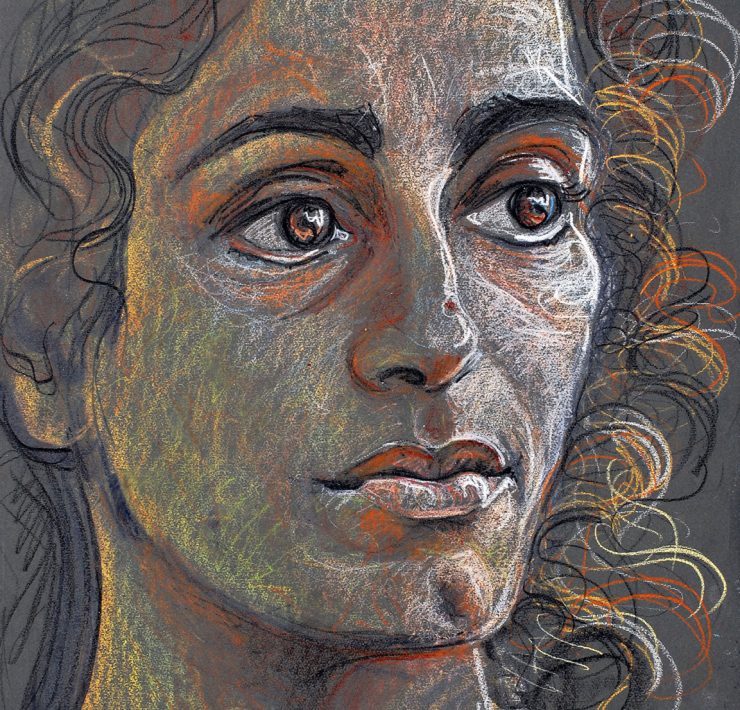

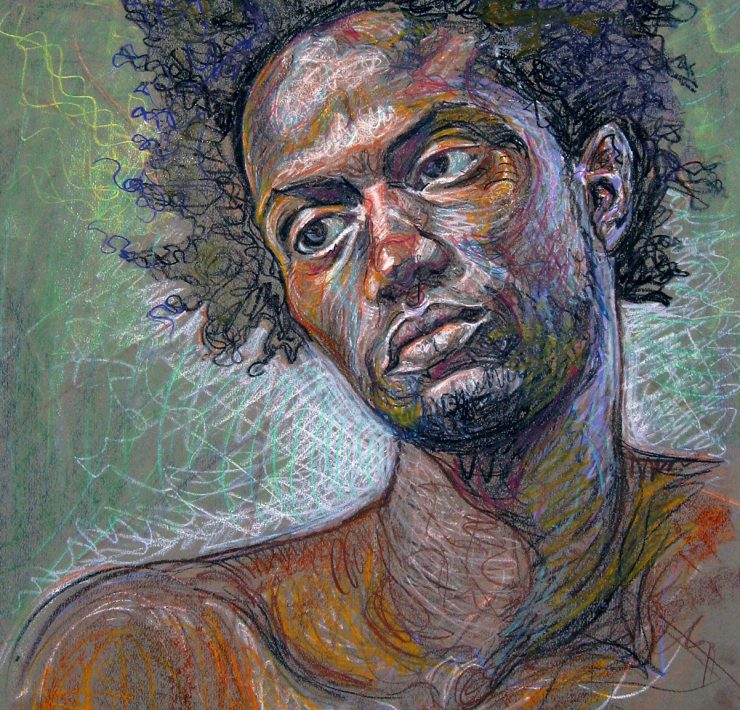

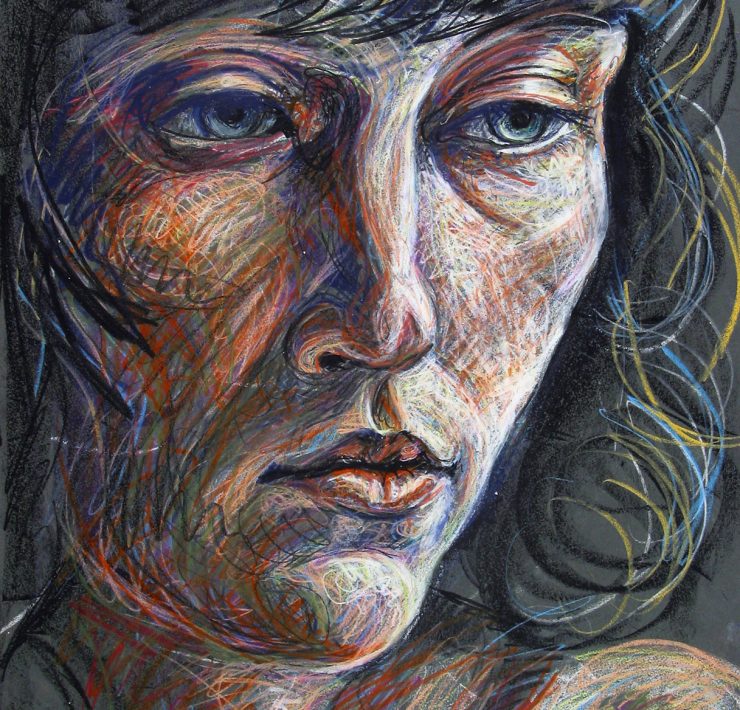

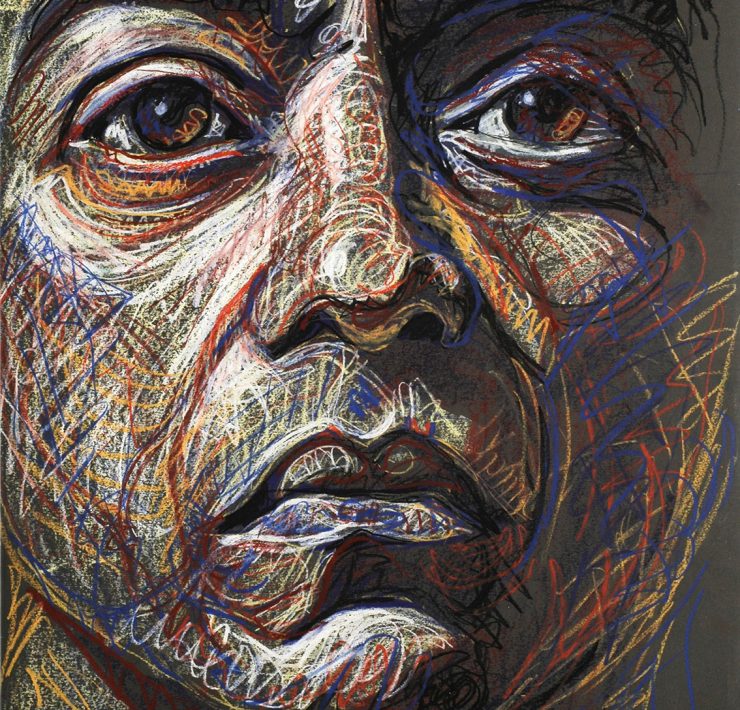

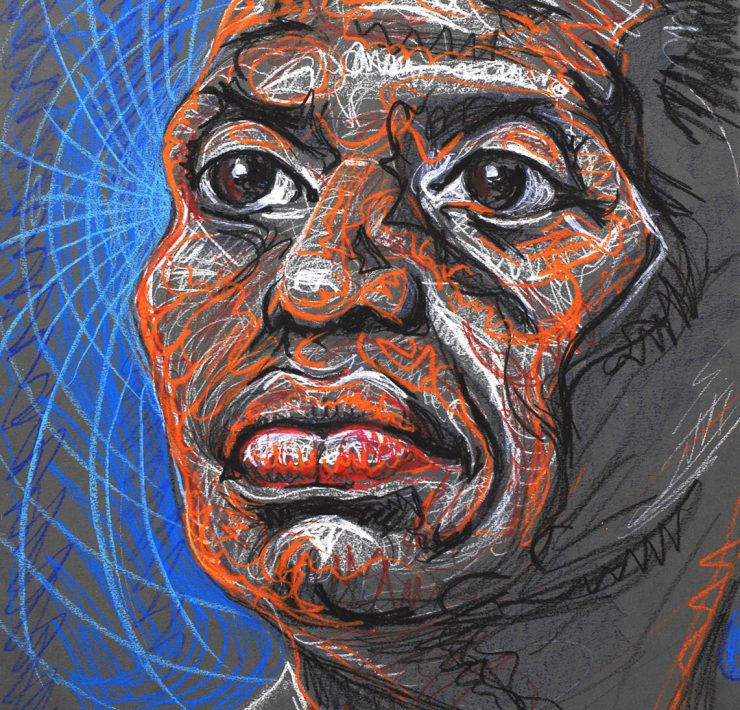

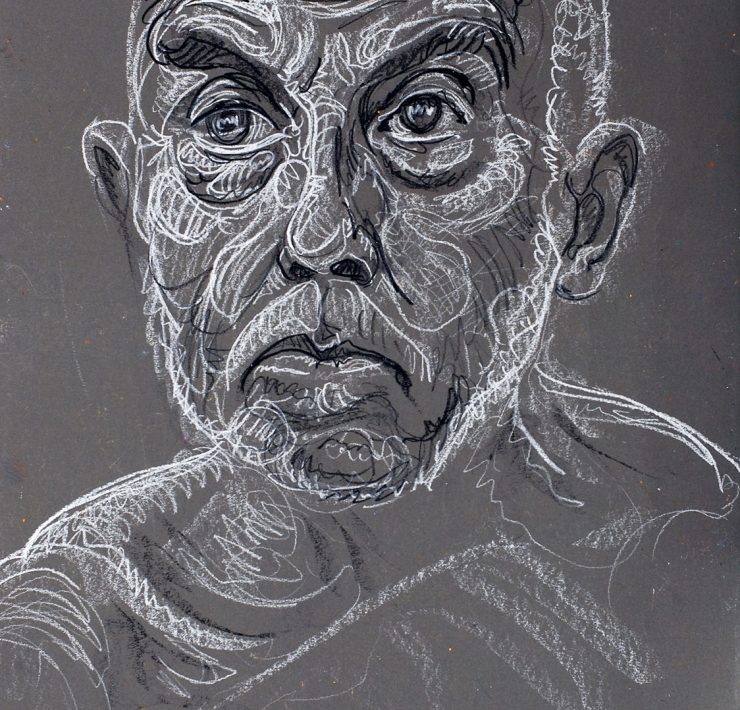

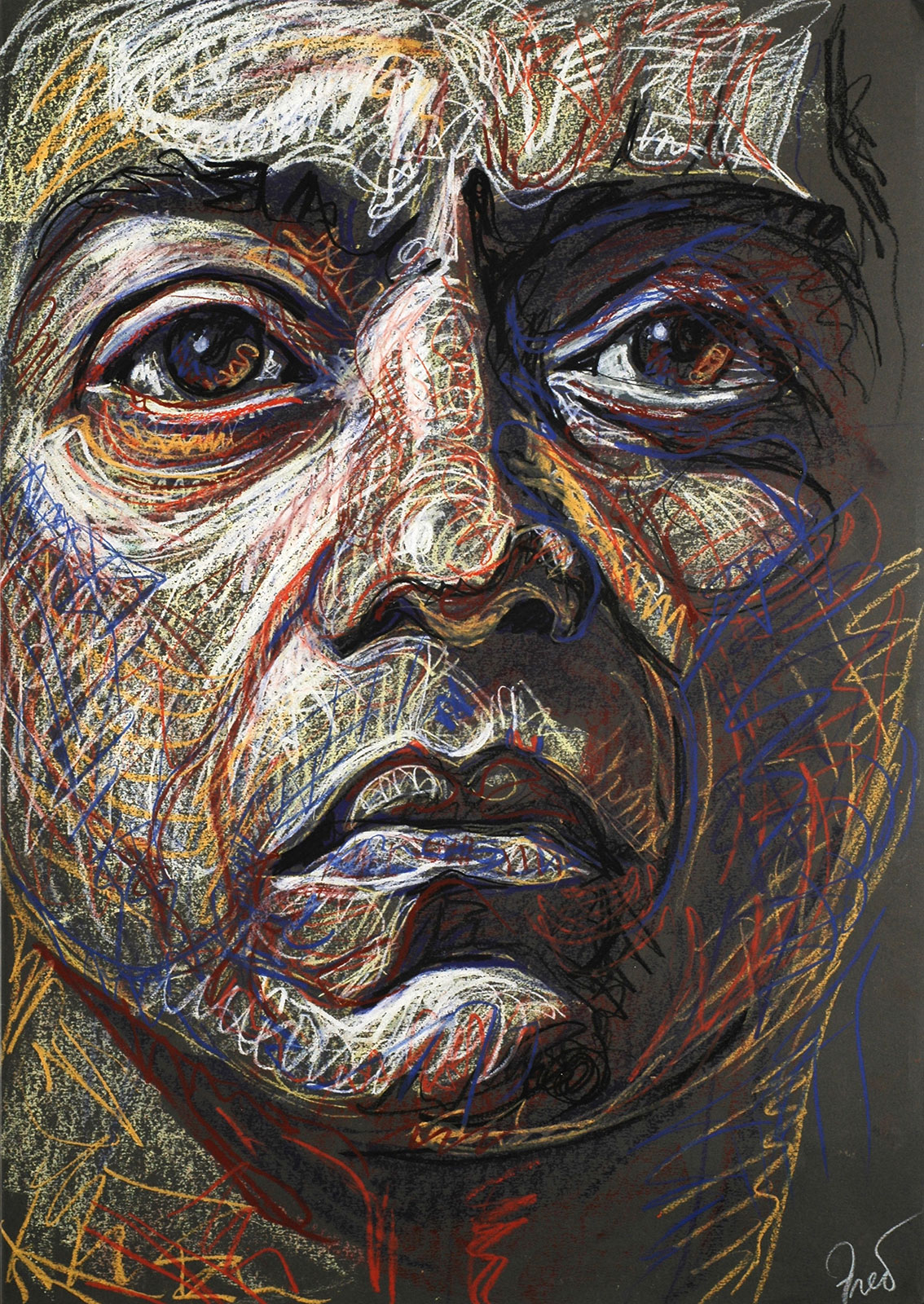

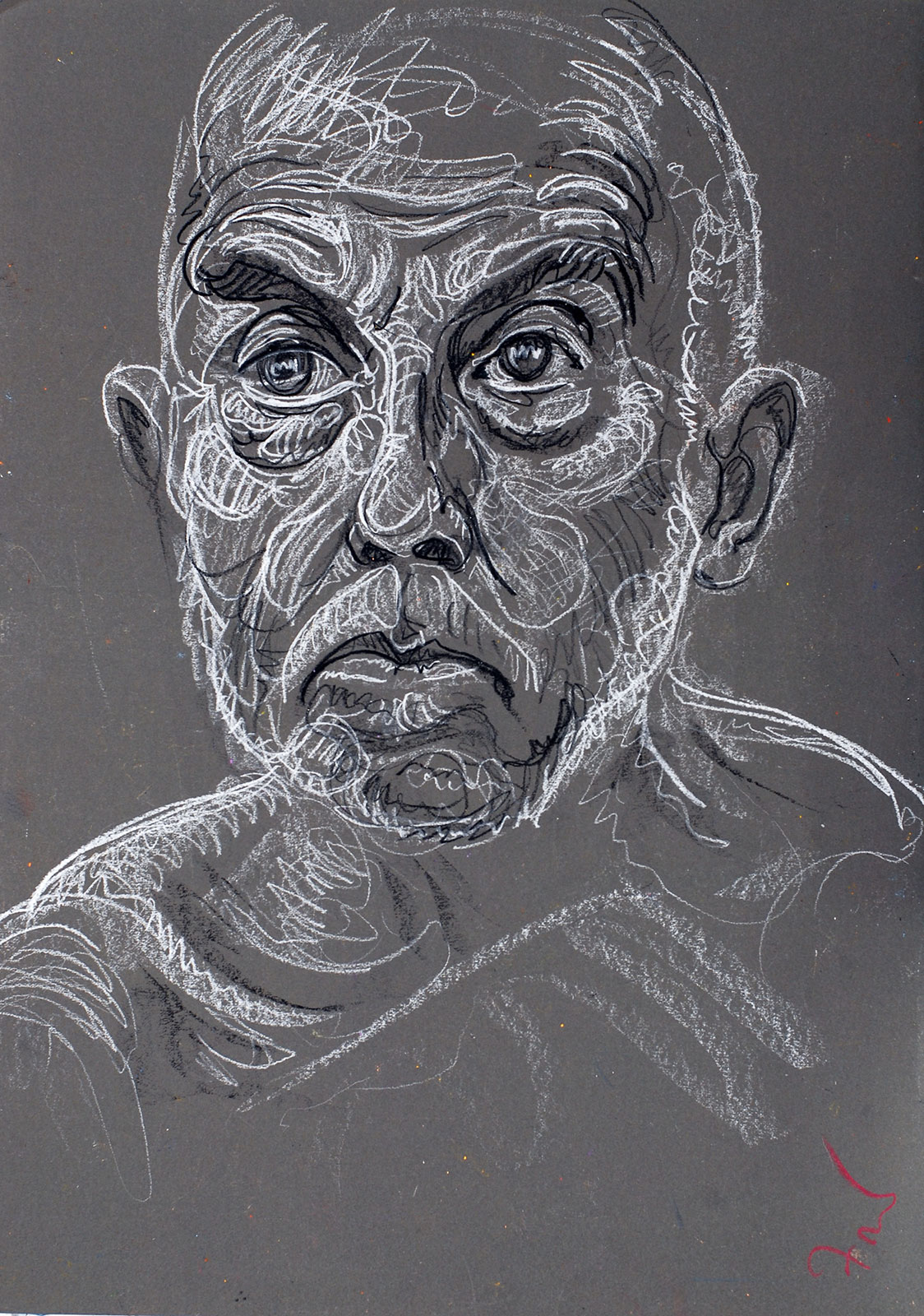

We hit it off immediately, sharing thoughts about art and the industry, the value in creative collaborations, our opinions on politics and culture. In the span of eighteen months, I got to know Fred on a creative and personal level. I’ve come to admire his dedication, craftsmanship, and vision. His capacity to see and internalize the depths of a subject’s emotion is clear through the vivid eyes he draws, which evoke an intensity that transcends medium or format, be it paper or video. I remain intrigued by the fluidity with which he portrays people.

Fred grew up in the 1960s and 70s in Enid, Oklahoma, a small city towered over by some of the largest grain elevators in the world. His father was a professor of theology and philosophy, and his mother was a writer and teacher. Fred grew up in a house full of cultural media, literature, and art books. “It was the era of psychedelics and movements for social justice and self-discovery, computers and space travel, and wild innovation in the arts,” Fred said in our interview. “All that culture made me a misfit in the Bible Belt, but it opened me up to a huge world full of possibilities. How could I be anything else but some kind of artist?”

Each art form embodies its own language. Fred chooses mediums that complement and saturate his artistic vision, which speaks to the breadth of his skill and sensibility. I’ve learned that just like he combines craft with intuition to connect with a subject, Fred also carries a personal sense of connection to the world, but as an outsider. Living as an artist, as the other, frees him to travel the outer realms of our collective experience and to push against the boundaries of time and space. I hope his journey inspires, particularly his perspectives on art culture and the art of expression through multimedia and mixed media, which he has done for decades.

The Daring: Who are your influencers?

Fred Hatt: All art has some kind of magic about it. Base materials like paint or stone are imbued with a life force, able to change the way we feel or see things. I am obsessed with understanding that magic.

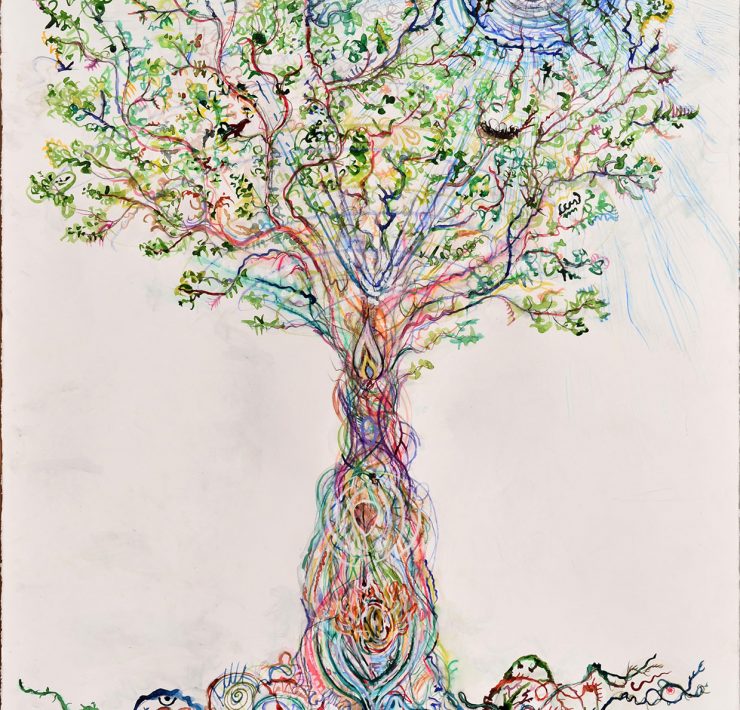

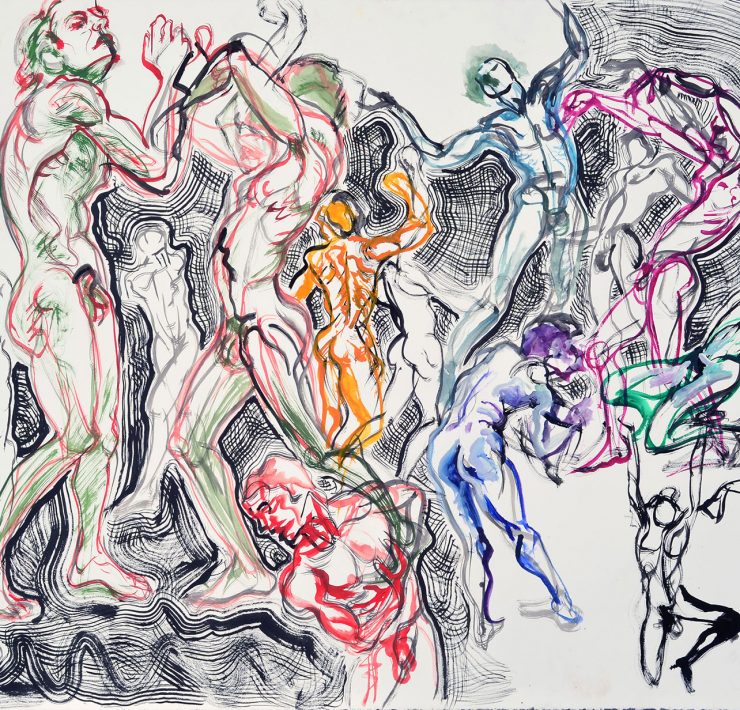

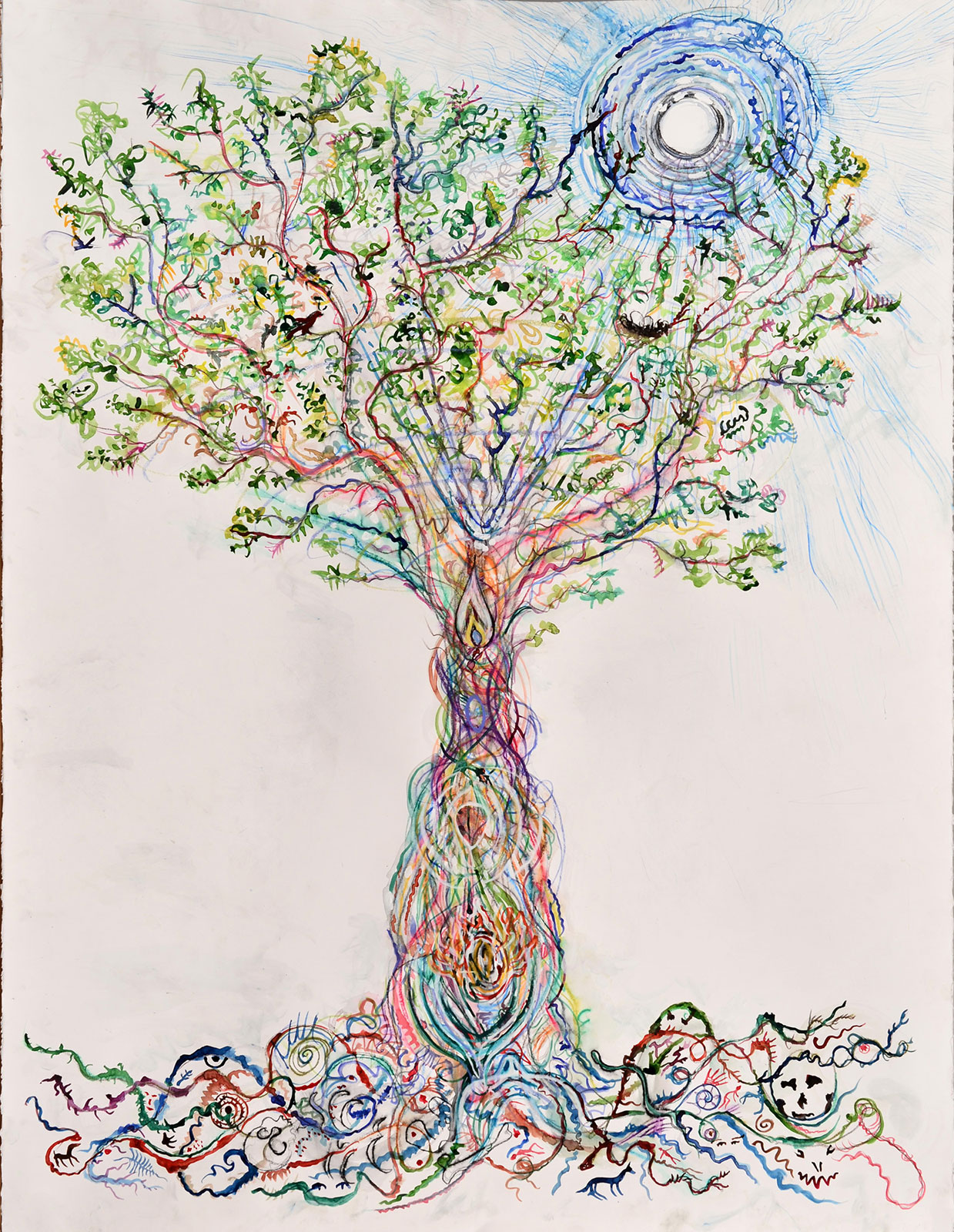

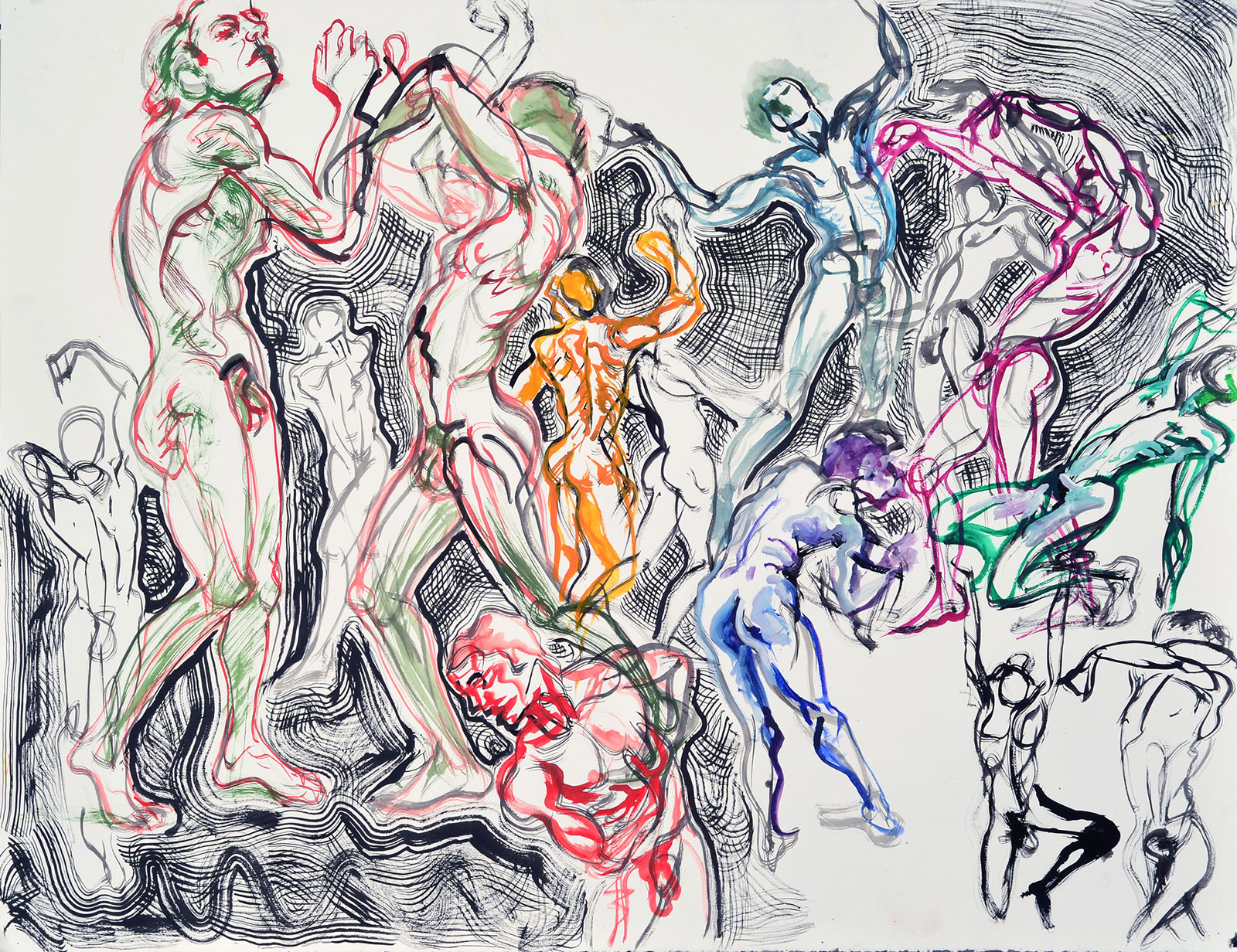

Some of my influences have been Michelangelo, Goya, Rodin. I am inspired by Taoist philosophy, I Ching, the ancient divination system that embodies a philosophy of change in a random-access poem, magical philosophies, physics and cosmology, Zen koans, Taoist fables, energy anatomy. Psychedelic/sacred/mystical art, erotic art. Experimental and subversive film, Avant-garde arts, performance artist Frank Moore. I get inspiration from traditional tribal art forms, ritual, and music.

TD: What drove you to pursue film? How did you land in NYC?

FH: The art of filmmaking seemed to combine movement, stories, music, design, and photography. I went to film school at the University of Southern California, but soon realized I was not good with popular narrative forms, so I felt creatively adrift.

I married and spent most of my 20s experimenting with painting, writing, and creating. I lived back in Oklahoma and felt isolated from any kind of scene or cultural ferment. My wife, Kate, was a writer and got into a playwriting residency in New York City, where we moved in 1987 and split up almost immediately.

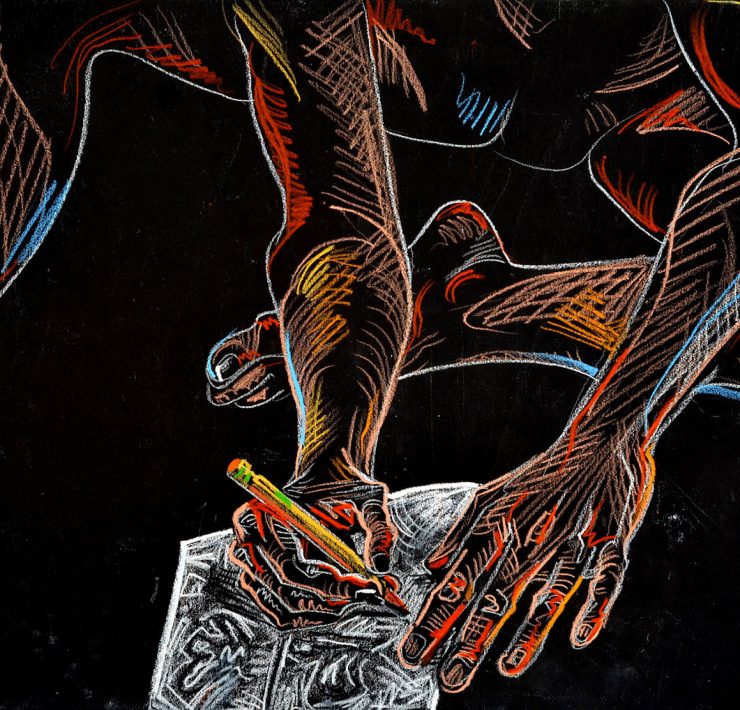

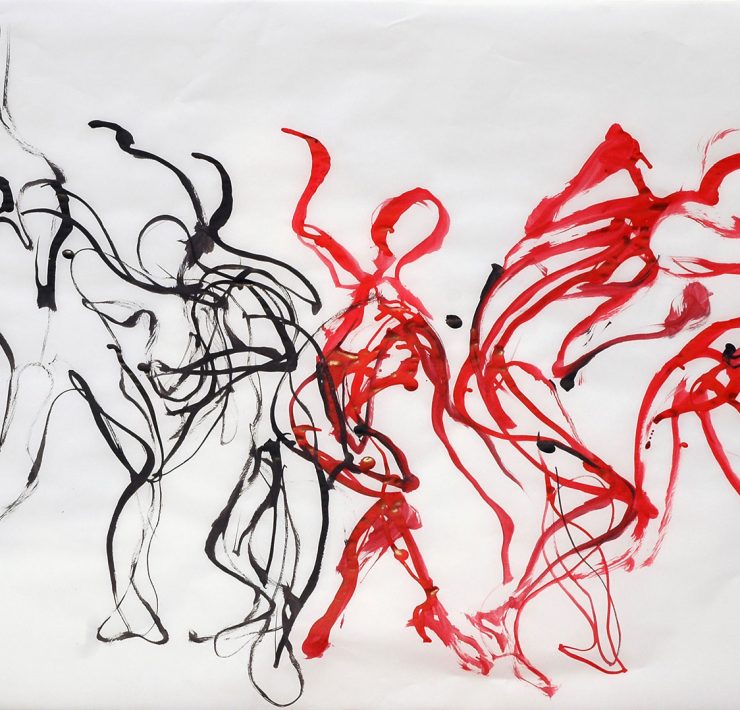

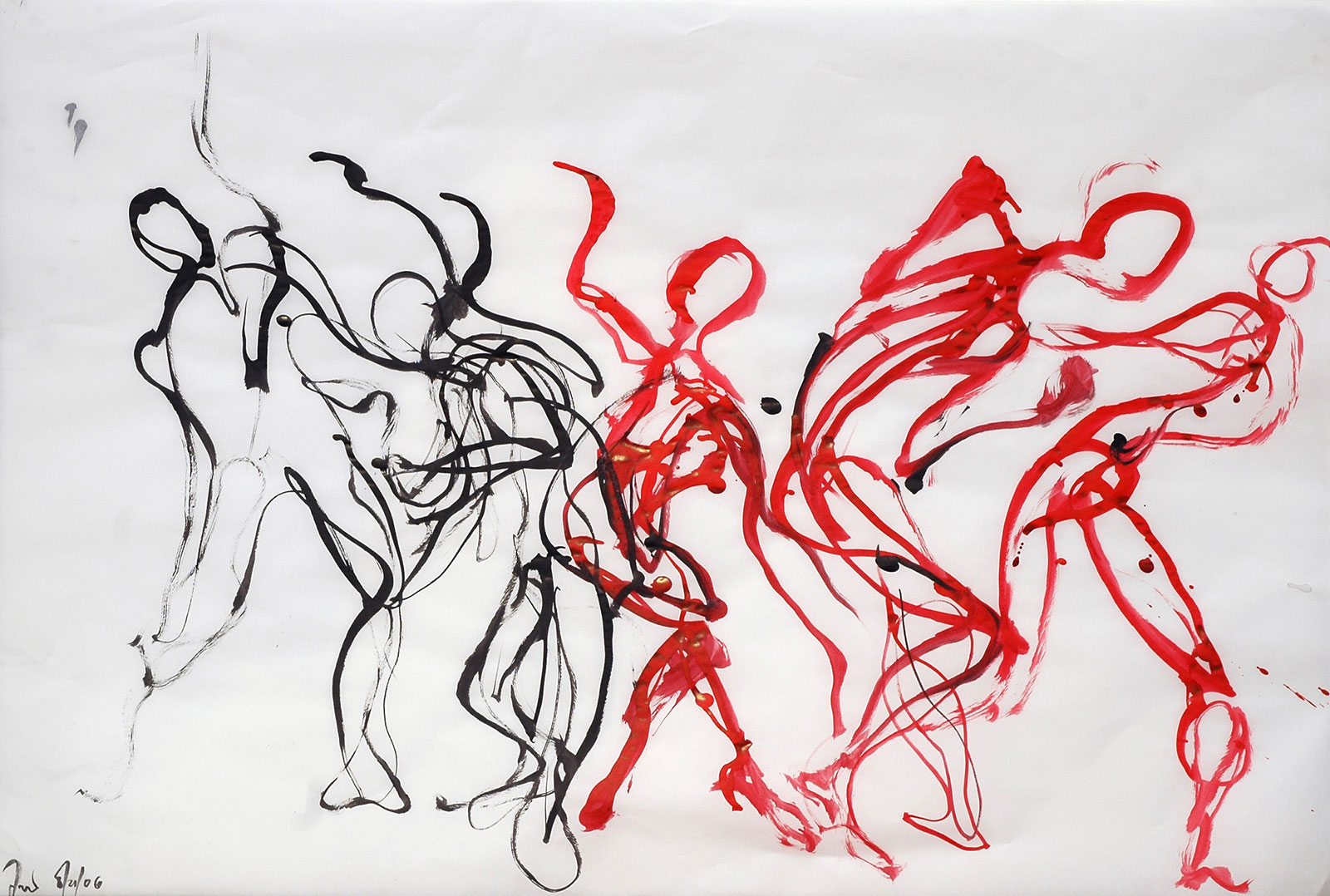

This was my rebirth as an artist. The creative anarchy of New York in the 80s and 90s was super-energizing. While working at a Media Arts Center, I produced a graphic novel, experimental video art, multimedia performances and installations, abstract and figurative paintings, stereoscopic photography, experimental photography, body paintings, and dance performances. Body painting, in particular, became a major component of my work for years to come. In the ’90s and 2000s, I did a lot of improvisational dance, performance art, and collaborative work with painting combined with dance and music.

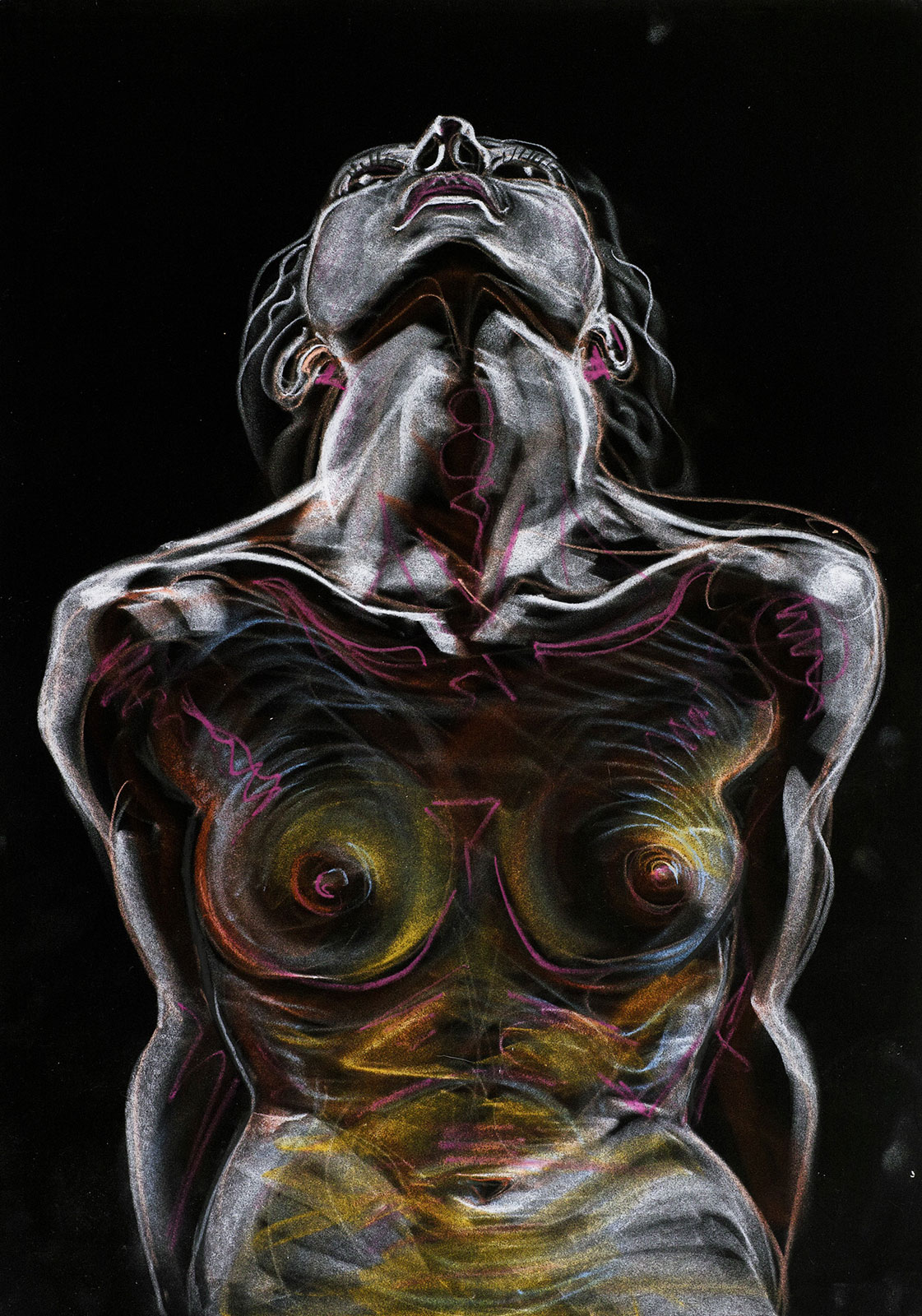

TD: So much of your work focuses on the human body. What draws you to it? What steers you, and is there a connection between the subject and materials used?

FH: If you look at my list of influences, the body ties many things together: sacred, erotic, magical. Embodiment is the central fact and the central mystery of the human condition. We can only experience the world in the form of a body that is inherently temporary. The body’s movement is the basis of human expression, whether through acting or dance or the gestural quality of a brushstroke or a musical note.

Rudolf Laban, who created a language for describing dance, lists eight efforts or qualities of motion: wring, press, flick, dab, glide, float, punch, slash. These could equally describe different brush strokes or charcoal marks that an artist might make on paper or canvas.

In observational drawing, we glance back and forth between our subject and our drawing, constantly picking up small impressions – a curve, an angle, a color – each fragment of seeing becomes a mark on the page, gradually building a coherent image. In this way, a drawing is a record of the act of perceiving.

When collaborating with a model or a dancer, it’s a pretty loose collaborative process, and it never worked well for me to try to stick to a script. I enjoy working with others because painting or writing alone can feel isolating, but working with another person brings a give and take to the process; happy accidents that you couldn’t have planned happen.

TD: As a male artist, can you talk about your relationship with the female body and how it’s perceived in contemporary art and art history, particularly as a subject/object?

FH: When I chose figure drawing, I was aware of the feminist and post-colonialist critique of traditional nude art as the male gaze, as a way of objectifying, othering, and claiming ownership over the bodies of people less privileged than the elite artist or his patrons. My approach to try and avoid the pitfalls of the male gaze is to see the model as a subject, not an object, to focus on the life force or energetic pattern of the body and the person, on their essence and agency. I strive to portray what the model projects more than what I project onto them. I want to see the human body as a site of liberation rather than enslavement.

In a 2009 essay on my blog, Drawing Life, I wrote, “For me, the nude is an image of unity, of spirit incarnate and matter imbued with life. A work of art is in itself an attempt to put living energy into a physical form, so the subject matter perfectly fits the activity. The nude hides neither its eroticism nor its mortality, but shows the human as a cell of the body of Earths. The nude is a talisman to heal the ancient division afflicting humanity [mind-body duality], and an assertion of freedom and joy against fundamentalism and fear.”

TD: Your art is often accompanied by text. Tell me about your relationship with language and art?

FH: Art is a kind of practical philosophy. To think philosophically, we need abstract concepts, metaphors, and reasoning. I write because a lot of what I want to express can only be said in words. Writing plays with the sound and feel of words, the way words look and relate to the page. A particular word or phrase can have the same evocative power as a color or a gestural mark. The combination of sounds, images, and feelings can be analogous to the composition of a painting or a piece of music.

My use of language is heavily influenced by a decades-long study of ancient Chinese writings, particularly the I Ching (Yijing) and the Tao Te Ching (Daodejing). In the ancient form of Chinese, a written character represents a whole range of concepts. A juxtaposition of characters can express more by evocation than by any modern parsable sentence structure or rational argument.

TD: You see-saw between abstraction and figure drawing. What compels you to move between the two?

FH: I always needed to have multiple forms to explore. In observational drawing, the focus on a subject grounds the work in physical reality, and I strive to capture a sensory experience. In abstraction, the grounding is more in the physicality of the materials — the brush, paint, paper — and the hand is free to explore its movement impulses, rather than following the eyes.

Life drawing and urban landscape photography are also regular practices for me. For over 20 years, I have had a camera on me when going about my daily business, keeping my eyes open for ordinary things that seem remarkable because of a momentary effect of the light, a striking juxtaposition of pattern or color, or just the complex strangeness when seen things deeply.

TD: What recent changes have you noticed in the art world that surprised you or that you were happy to see finally evolve?

FH: Art institutions create boxes to separate art forms, and the academics and curators create narratives and discourses to connect the pieces. I just went my own way, making art as a personal creative practice, the way people practice meditation or gardening.

I presented my work in underground scenes and alternative venues — tattoo parlors, gymnastics studios, churches, warehouse art events, and pop-up galleries. I did performances in nightclubs, burlesque theaters, life drawing studios, rooftops, midtown Manhattan storefront windows, and public parks. And I did demonstrations, workshops, presentations, and screenings at dance festivals, pagan gatherings, and educational institutions. And now, I increasingly share work through the internet.

The growth of the internet has made it possible for anyone to share their art with an audience, which is great, but it has also increased the number of images and media that we encounter in our lives to such an extent that it has really diminished their power and magic. In the age of social media, there is such an endless torrent of images, and everything just gets sucked into the vortex. Things “go viral” not because of quality, subtlety, or depth. Who has time for that these days? I rarely approach the creative process with big ideas or ambition, and my artistic practices are just a flame I keep burning at a low level all the time.

TD: What advice would you give to young artists?

FH: Don’t take on crushing loads of debt to go to art school. If you want to learn the business of art, being an assistant or apprentice to an artist, or working for a gallery or institution, may be more valuable than having an MFA.

Most of what alienates people from contemporary art is the academic domination of the field — concept dominating over craft, trendy ideas taking precedence even over the experience of encountering the artwork. It leads to all those impenetrable and pretentious wall labels and work that often lacks a certain magic.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Fred Hatt is a multimedia artist living and working in New York City. Visit fredhatt.com.