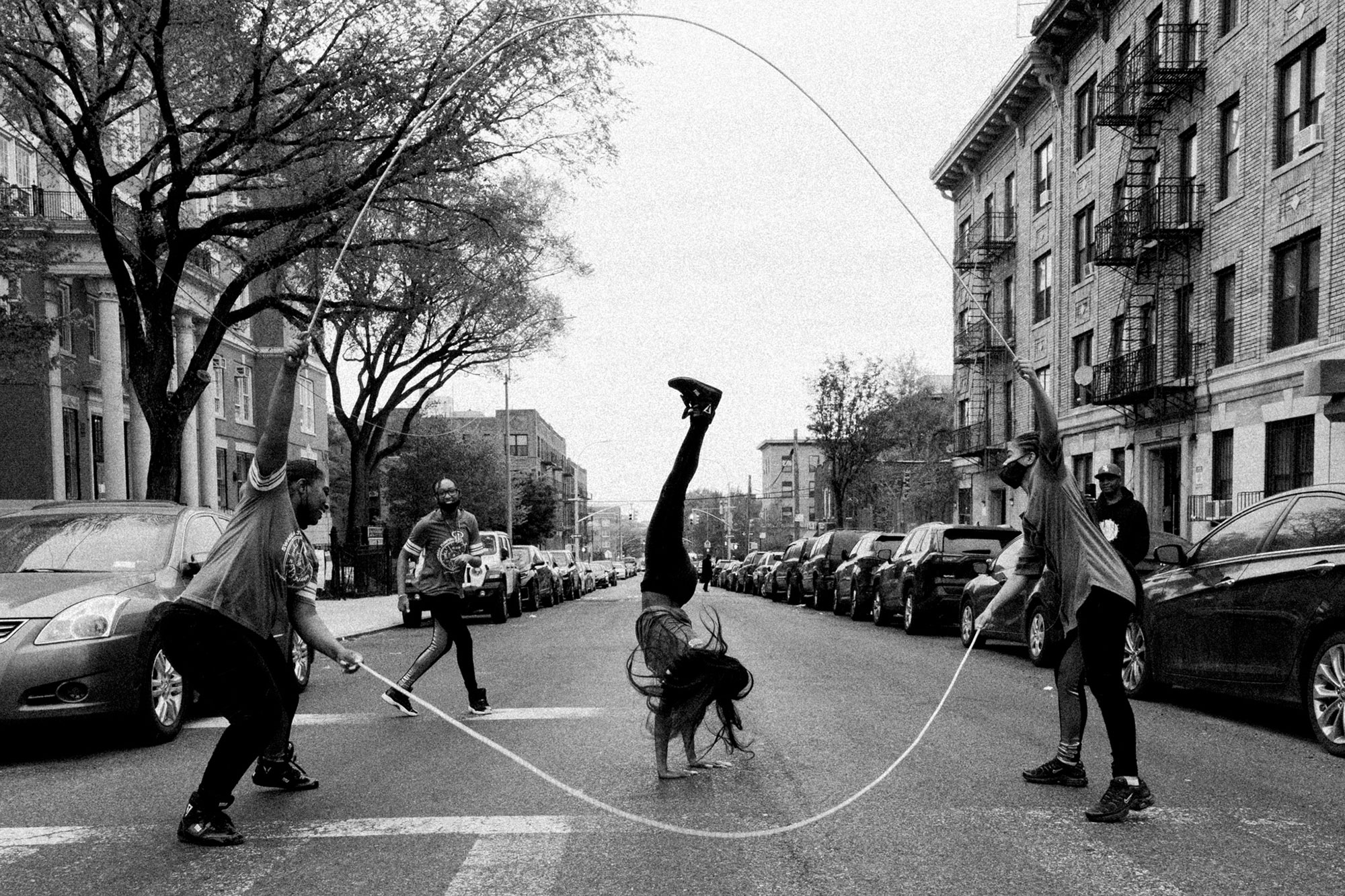

Girls Who Fly: Photos Celebrating the Power of Double Dutch

Chris Facey highlights resilience and the importance of community through photos of double Dutch that leap with overflowing joy.

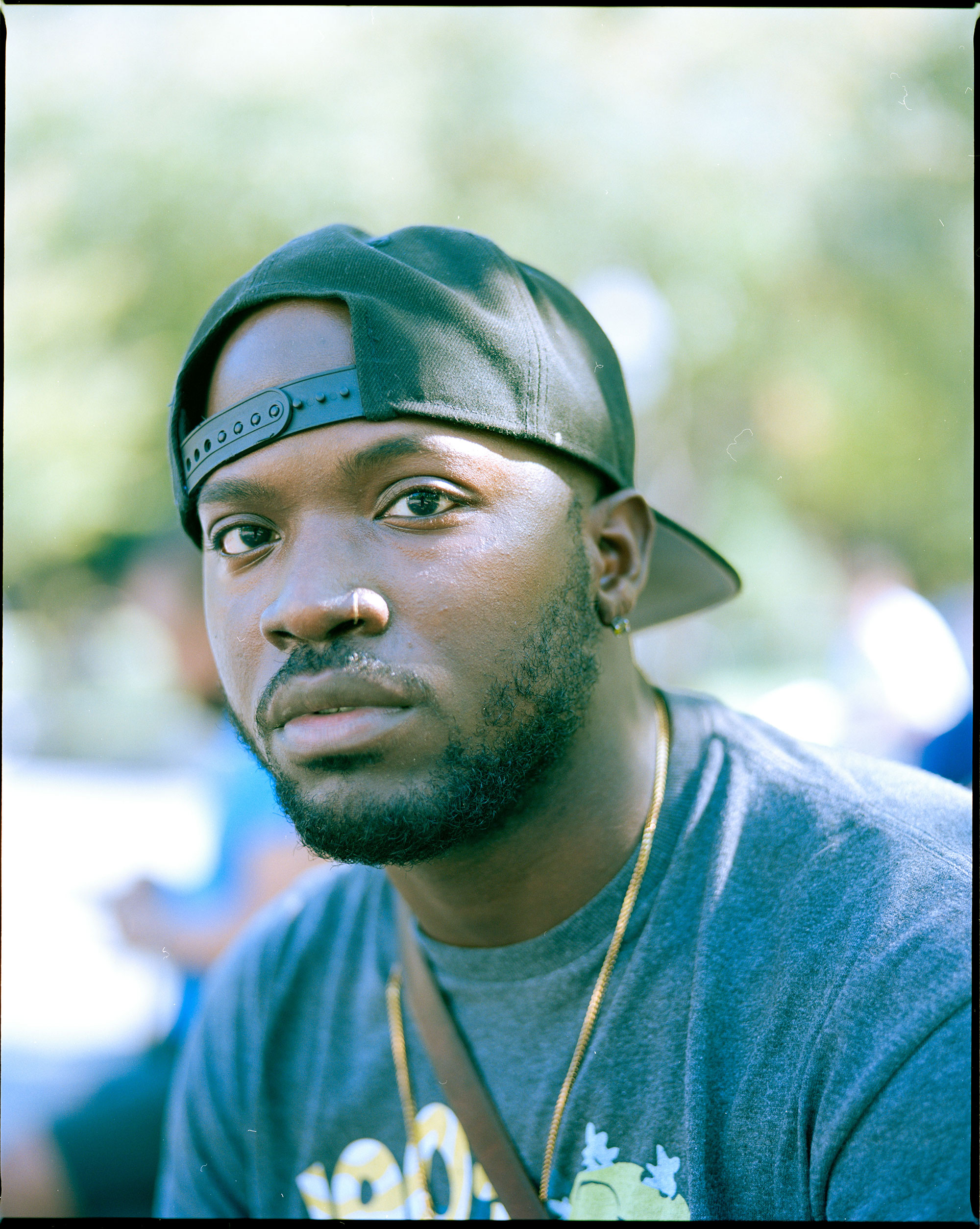

Chris Facey is wrapping up prints for an exhibition. It’s about ten in the morning, as we meet on screen. He gives his double Dutch photos another look, noting that he’ll drop them off with a curator later today. He’s framed them twice; the first time, fibers and dust snuck in below the glass, which he noticed after he stood them up. He leans in and lifts up his baseball hat. “I don’t even have any hair, so where is this coming from?” he laughs. He’s charming and confident, no doubt — and also an artist who savors doing the deep work of preparation.

Since 2020, he has photographed myriads of double Dutch scenes, documenting this ever-expansive cultural pillar for generations to come. Coaches and kids leaping, flipping, resting, competing, laughing, thinking…the feel is effervescent, tender. In one frame, a girl hovers in suspended animation at the top of a jump (her T-shirt reads #ropelife). You can hear the rhythm of the rope throughout.

His work, including this series, has animated stories in The New Yorker, The Cut, and The New York Times. He’s becoming known for his commitment to his job: researching deeply, getting as close as possible to the source so that he can “have an honest conversation with the people” he comes across. Like many visual journalists, he has highs and lows, stories he’s eager to dig into, and stories he’d rather not think about “for at least another 10 years,” like the protests of 2020.

Now, he is busy grounding himself as a photographer in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he just moved from his native New York City. He speaks without haste, and has a mild way of finishing sentences. We stroll among topics that include parenting teens (complex), the power of partnering with a great writer (golden), careers in dental hygiene (a no go!), and how to get into documentary photography (by avoiding a career in dental hygiene, of course).

Double Dutch is a long-term documentary project. Life-long, even, as he is personally invested in the projects he takes on. He sees photography as a unifying medium, given the right context — one that can preserve culture, that can facilitate understanding between multiple cultures; opening up dialog and dispelling stereotypes at once.

The Daring: What inspired you to document double Dutch?

Chris Facey: The day I had the idea, my daughter was with me, and we went to the Brooklyn Museum. Right outside the Brooklyn Museum, there was a Jump For Justice event. That was the first time I got to see my daughter jump and try it out, see how nervous she was, and how excited she was. And they taught her how to jump in five minutes.

But the whole feeling about that event was, Yo, I don’t really get to see people jumping rope anymore. It just reminded me of a different time, you know? I remember when I was a kid, you came outside, and that was a thing. Jumping rope, jellies on the feet, and doing little dance moves and killing it.

TD: How do you think being a parent influences your approach to this story?

CF: Being a parent, you got to anticipate things, and with documentary photography, the name of the game is anticipation. You got to have foresight into what’s happening. Sometimes you got to just take your time.

So both in photography and then life, especially in conversation, you got to let people say their piece, say how they feel. Then you see what part you want to take and how you want to analyze it. Simple and plain, you just have to slow down and allow things to unfold before you make a decision, before you react, before you do anything. So it’s allowed me to be more patient. I stuck with it, watching jumping rope be a stronghold for young Black girls. And I’ve just been chilling with the coaches ever since. Talking to them, getting their understanding about the importance of jumping rope and how long they’ve been doing it, and why they’ve been doing it. It’s important.

TD: Who do you primarily create photos for?

CF: My work is always for the Black community, all my Black brothers and sisters. I want to make sure that our history remains our history and stays part of our future. Jumping rope is, as far as I’m concerned, from our culture. I know the history, that it came over with Dutch settlers. But what most Black people do, we take something, and we make it new. And now it’s dope, now it’s fly. Now you get it.

I don’t want the community to forget that we know how to take nothing and create greatness with it. So that’s the goal with my work, to focus on the Black community. That’s where my heart is at, and I like to shoot wherever my heart is.

TD: It’s clear from the amount of time you spent with the coaches and the kids, that you put a lot of heart and research into developing this story. What kind of background work do you do?

CF: Before I do any research on something I think I want to dive into photographically, I have to care first and foremost. Doing research on something I don’t care about makes it tough to get through, and that will show in the work. Once I start doing the research, it becomes intensive. I just keep digging and digging. I reach out to people and ask questions. Watch documentaries (if there are some), videos, and old articles. I try to get as close to the source as possible. Learn as much as I can so I can have an honest and genuine conversation with the people I come across.

TD: When you look at visual storytelling out there, what big shift do you want to see in publishing?

CF: Bring back photo essays. Have photographers go out into different communities and allow them the time to make the connection, build a rapport in these communities, and let them do what they do best as storytellers. Let photographers link the story that is and bring it back. Focus on topics that are important to people’s feelings, win the hearts and minds of people.

TD: How do you go about developing a strong plot in your stories?

CF: Some of your favorite movies, you care about because the storyline is good. Some of your favorite books are simply that, just a really good story. Whether you write poems, making photographs or videos, writing a story, whatever it is, there are certain elements that go in there to make people care. But I can’t just give you, This is the beginning. This is what happened at the middle. Here’s the end. There’s so much context in between those three parts, and that’s where we shine as creators, and that’s what we bring to people.

TD: How do you think about framing the double Dutch story? Where does the narrative start for you?

CF: You can find countless articles, videos, and photos online about the history of double Dutch. And if that is what you’re going with, then that’s where your beginning will be. For me, my beginning was showing this important part of girlhood.

Not to say that there aren’t guys that jump rope. I photograph plenty of young boys jumping rope. But for the young ladies, I notice that it’s this whole sisterhood, this thing they connect over. You start battling things a lot of young women suffer from, like being insecure or lacking self-esteem. I’ve seen jumping rope change that in young women. So I want to show that resiliency, that growth.

You see, from the outside, it looks like they’re just having fun jumping rope. But there are countless hours of practice that go into this. There are a lot of self-doubts that go into this. I watch these girls get angry and upset if they mess up a jump or they can’t get it, you know what I mean? And watch them keep trying. And they’ve done all of this to give you about two or three minutes in the rope.

There’s something to say about that. These are young girls, and these are skills that they’re going to bring into adulthood. That is the beginning of the story that I’m trying to show. In a perfect world, I would follow one jump roper for the whole entirety of their life. I also want to go to Nigeria, where they have double Dutch schools. I’d like to show how double Dutch is in a lot of Black communities across the world and put it in a book. Show how this one rope is the one thing tying them all together.

TD: Do you feel like developing this story has changed you?

CF: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah. I can’t even say no, because then the photos wouldn’t work, you know? The photos wouldn’t work if I wasn’t taking it as change too. As a parent, I had to step back and let the coaches coach. If my daughter messed up, I wanted to go in there and give her these words of encouragement, but I had to fight the feeling. It’s not the time for that. Because if I wasn’t here, how would she get through this right here? So I let the coaches handle it.

And I saw a different learning style, a different teaching style. I saw how my child fares with not getting something on the first go-round. And then, I’m able to identify it in other children, Oh, I understand. Okay. I see. I see. And then I take some of those tactics, and I go back, and I use them with not only children but with adults. Different teaching styles, different speaking styles, different encouragement, letting them know when they’re messing up and how to get better. Or when I’m messing up.

I also learned to not expect people to do anything that I’m not willing to do myself. One thing I can say about the double Dutch coaches I worked with, especially Laila [Little-Omosawe], they will get in the rope. She’ll show you, I seen the flip. And when the kids are frustrated, she’s like, “I’m not asking you to do anything that I’m not doing.”

That’s a regular day for a coach. But me, I get to take this whole scene in, and it’s like, All right. All right. I’ve become more open to learning and teaching. I will not get in that rope, though.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Chris Facey (b. 1990) is a photojournalist and portrait photographer raised in Brooklyn, New York, and residing in Raleigh, North Carolina. Inspired by the works of Gordon Parks and W. Eugene Smith, he documents communities with softness and allows space for emotional depth while still covering hard-hitting issues such as racial injustices in civil rights and women’s safety in New York City. A School of Visual Arts BFA graduate and an Army veteran, Chris is on a strong path to success with his photodocumentary projects, which have landed him opportunities in publications such as The New Yorker, New York Magazine, The Cut, and The New York Times.