Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Rachel Wyman’s Meditative Return to Her Most Natural State

Dancing in the fields of Walla Walla and in the rooms of a Brooklyn psychiatric ward forces Rachel Wyman to reconsider a traditional path to dance movement therapy and inspires her new paintings, “Blue Pajamas.”

At the height of the pandemic in September 2020, I was scrolling Instagram — like many of us did out of boredom or because we were obsessively distracting ourselves from our harsh reality. I stumbled on Rachel Wyman, whose short, visually evocative videos transported me into a different realm, beyond Walla Walla, where she recorded them, which I later found out. Her body movement was hypnotic, as she blended with nature, moving through sandy hills like an ophidian, or standing on a dirt road with blues in the sky drifting, coinciding, and diving into the earth. Her pieces, infused with spoken or written language, added yet another curve to the imaginative ways we as humans crave to express ourselves.

Here is a quote from Inevitable Grace by Piero Ferrucci, psychotherapist and philosopher, that Rachel paired with one of her video pieces: “The word humility, also human, is derived from the Latin humus, meaning ‘soil.’ Perhaps this is not simply because it entails stopping and returning to earthly origins, but also because, as we are rooted in this earth of everyday life, we find in it all the vitality and fertility unnoticed by people who merely tramp on across the surface, drawn by distant landscapes.”

Rachel’s work forced me down a rabbit hole. I watched dozens of her videos, swayed under her spell, tempted to DM her. So I did, asking if she’d want to meet up for coffee and perhaps collaborate on an art project. Of course, within weeks, we were working on a hybrid piece incorporating one of my poems and her body movement in a video called “Who Said I Can’t,” produced by our now mutual friend, Fred Hatt. The piece blends performative poetry, dance, art, and video to inspire dialogue about the idea of retaining command — one’s right to personal experience, self-expression, and self-exploration — particularly from a female perspective.

Rachel’s organic movement, paired with graceful shadows, guided the viewer through the poet’s language, attempting to dismantle the silencer while obeying the poem’s structure and constriction. Like the poet, she tries to manipulate boundaries while simultaneously exploring the outer spheres of self and the possessor. Of course, in Rachel’s case, that’s nature in all its vastness. The poem visually reflects on desire and plays with the idea of self-restraint. Through progression of gesture and merging with the forest, its trees, the earth, wind, and sunlight, Rachel connects to her natural surroundings with uninhibited fluidity.

Since then, Rachel and I have had many conversations about various projects, but one that stands out is her recent set of paintings, “Blue Pajamas.” I sat down with her to talk about the inspiration behind it and how it relates to her experience as a dance movement therapist at the psychiatric ward of NYC Health + Hospitals in Brooklyn. “Dance and creative art therapy is another form of psychotherapy that uses movement, art, and music to help people express, uncover and discover themselves,” Rachel said in her interview.

Speaking with Rachel about her experience and learning about “Blue Pajamas,” I realize how easily we, as individuals, could lose our sense of identity — and how crucial it is to retain a sense of command and one’s right to personal freedom. We mostly obey structures set forth by governments, institutions, our communities, and even ourselves, within which we are meant to uphold a type of standard, whatever that may be. However, I understand from Rachel and her body of work that we mustn’t forget to explore the inner and outer spheres of self simultaneously — even if we’re confined to an idea, a space, or mental and physical constrictions. We are all swerving between selves and our own shadows.

The Daring: Tell me about your development as a dancer and the kind of dance you practice.

Rachel Wyman: As a movement and body-based multidisciplinary artist, my first art discipline was always dance. As a child, I started ballet, which I quit shortly after because I did not like the restrictions it put on the body, and the preciseness of it did not work well with my inner self.

I attended Oberlin College and later went to Mali, where I studied folkloric Malian dance with Bintu Keita, one of the lead female dancers at Les Ballets Malien. And while a member of Kotchegna Dance Company, run by Vado Diomande, I studied traditional Ivorian dance and drumming. My Haitian mentors in New York, Adia Whittaker, Julio Jean, and Peniel Guerrier, were incredible sources of inspiration — not only for teaching me the movement of the dances but also for educating me about the spirit and history behind them.

I also learned so much through the anthropological/ethnographic work of Katherine Dunham, Maya Deren, Yvonne Daniel, and Robert Farris Thompson. During college, I delved into various West African and West African diaspora dances and dances related to the orisa (also spelled orisha, or orixa). The orisa are deities/spirits originating out of West Africa, among various ethnic groups of Nigeria, Ghana, Benin, and Togo.

The orisa traveled with people to the West Indies and North and South America, sometimes taking on slightly different forms. With Haitian Vodou, for example, West and Central African religion intermingled with Catholicism and probably the cosmologies of indigenous Carib, Arawak, and Guanahatabey people of the island (which was called Hispaniola before it was Haiti and the Dominican Republic). In Haiti, the spirits are not called orisa — they are called lwa (also spelled loa).

The dance called yanvalou (also spelled yanvalu) is performed in ceremony for a lwa called Damballah (also spelled Dambala, or Damballa), symbolized by the snake. It is the “New World” iteration of Da, a god of the Fon people of Benin (which used to be Dahomey). Katherine Dunham describes Damballah as a “symbol of continuity, the roundness of time, of indestructibility by time.” There’s a Dahomean explanation of Da that I absolutely love — it was recounted to anthropologist Melville Herskovits, or at least this is how he recounts it: “The vodu Da is more than a snake. It is a living quality expressed in all things that are flexible, sinuous, and moist; all things that fold, refold, and coil, and do not move on feet.”

Yanvalou is a dance that embodies that idea — it’s characterized by a beautiful spinal undulation that is sort of meditative, almost hypnotic to do and to watch. You can imagine the movement just going on forever. It has a circularity to it.

But while studying these dances and practices, I felt like I was treading a very fine line as a white person. There was often judgment or doubt regarding my intentions. However, I felt like my body was made to do these dances. It felt natural, more than ballet or modern dance, and it was just something my body was made to do.

TD: How did you overcome the challenge?

RW: I tried to stay out of the big conversations making sure that my professors and fellow classmates knew I was taking my dancing very seriously and wanted to learn more about it and really understand it. I was connecting to this practice philosophically, so it felt necessary.

Then, once I came to New York, I started learning the Haitian dances surrounding Vodou, which compelled me even more to practice. I went to Haiti several times and started learning Creol, and the songs and drums, because all of these dances are of a piece, all connected and performed as ceremonies. You say Vodou here in the West, most people get freaked out, but Vodou is reverence for nature. Many spirits represent the intermediary between nature and the human world. And I found it to be beautiful and powerful. Growing up in Walla Walla, Washington, I already had a close relationship with nature, and these traditions were another way of connecting and understanding my relationship with nature.

TD: Despite the judgment from your peers, you continued to immerse. Not everyone has the desire to appropriate. If I am not mistaken, you appreciate what these dances and practices teach you, not for gain but for their beauty and for what they represent.

RW: I think cultures have been interconnected for longer than we think. Cultures intermingle, ideas and forms get incorporated into one another, or borrowed, or, yes, stolen for the profit of one group and not another. But I have no interest in profiting — I’m interested in understanding and connecting on a more general human level, finding the humanistic commonalities within what appear to be cultural or aesthetic differences. I discover parts of myself in unexpected places. There are aspects of Vodou that feel deeply personal and familiar — especially the reverence around forces of nature, and the mystery of existence.

In my practice, I let the idea determine what voice it wants to take. I believe in cultivating ideas and finding the right expression in any and all artistic mediums. Sometimes I have an embodied idea, a sequence of movements that wants to emerge. Sometimes it’s visual. And sometimes, the visual and the movement combine. So that’s why I returned to Walla Walla for years, set my phone on a tripod, and created these pieces connecting visuals and movement to the land. I am quite attached to the land.

And, of course, it wasn’t until I left home that I realized that the landscape surrounding us becomes a part of us as we grow up. When you move somewhere else and immerse in another environment, you realize your internal environment does not sync up. And so, I always felt something of this landscape and the rhythm, pace, stillness, and quiet within me. One of the things I discovered when coming back and moving with the land is that I am not one who moves quickly. My internal pace is a lot slower than what I encounter in New York, so coming to my natural habitat, where my body gets to be and embody the rhythm it wants and needs, is a great relief and release.

TD: In what kind of landscapes do you find that relief?

RW: I consider myself sort of an agricultural and rural product — what I saw was not forests or ocean but mostly rolling fields or wheat fields, a lot of openness, open sky, open space, a big horizon. The blue sky and the golden wheat fields are beautiful, and these colors really move me. Even the dryness and the dust, the smell of the air, it’s just something I identify with.

I don’t exactly know what statement I am making with my videos or if there is a narrative, but I want to see my body in the land moving. It feels like I am working something out. I am just not sure what. Through it, though, I am returning to my most natural state, being myself fully. Through this process of movement, which is nonverbal, I tell a story. Incredibly oblique and obscure, it expresses something about a person’s connection to the world and the body, whether you are conscious of it or not. And when looking at my movement, I sort of develop a certain understanding of what that attitude is.

TD: How did dance take you into the mental health field?

RW: I became a dance movement therapist, but it was a misguided idea that I somehow thought was the right one for me to do. Because who am I helping with art, right? I must use movement to be more effective and help others with my art form.

I worked at a facility in an underserved neighborhood in Brooklyn. There are a lot of folks from that area who are brought in for mental health treatment, inpatient psychiatric, and outpatient. I worked in the inpatient psych, where people stay anywhere from a week to, in extreme cases, multiple months. I worked with acutely ill patients for just about three years. I left because I needed a break, mainly because of the bureaucracy.

It’s hard to work in such a sprawling, unwieldy system where for the most part, the people working there — the psychiatrists, social workers, therapists — although they mean well for the patient, the system makes it so difficult for them. Patients are often forced into hospitalization and are presented as a danger to themselves and others. Of course, they are unhappy to be there. Many patients have come back several times, some even monthly. I started questioning the existing system — if it was working, or meant to keep people on a treadmill, only temporarily fixing issues. Ultimately, it was hard for me to see people not getting better, and I felt there had to be a better way to treat patients.

TD: How has that experience shaped your perspective on mental health? Are you part of the system?

RW: I left. I got the sense that some staff, particularly the psychiatrists, felt they knew what was best for patients at all times — sometimes at the expense of patients being able to advocate for themselves. I became very conflicted about the notion of helping and healing. I felt I was there to provide temporary relief from suffering for people who were in a situation that was hard to tolerate, but I didn’t know how much I was ultimately helping.

What I learned was that the system wasn’t working. There were judgment calls that seemed to be in the interest of making things easier for staff, not patients. If a patient became dysregulated but managed to calm down with therapeutic staff, they would still receive a medication injection just because it was ordered. So their self-regulation efforts went unrecognized, which left them angry, feeling like self-regulating wasn’t even worth it. The patients felt subjected to a system that treated them inhumanely. It did seem inhumane at times. But sometimes, patients are also not in control, and they hurt themselves, other patients, and staff. What are we to do? Everyone is trying to navigate a difficult system that is intended to help but sometimes harms.

TD: Who is the oppressor, and who is the oppressed?

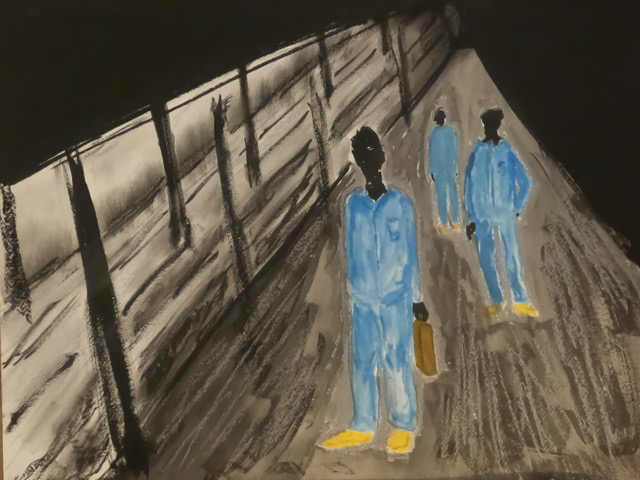

RW: Of course, in some cases, patients do need to be modulated because they are unable to self-regulate, but there has to be a better way. Even if it’s a matter of making the food better, or communication easier, or if the place doesn’t look like an institution, one that forces them to wear a Mental Illness uniform — these ill-fitting blue pajamas — like inmates.

I have become skeptical about certain words, like healing. I associate it with power — it suggests there is some all-powerful person who is capable of healing you when you can’t heal yourself. I think helping professionals sometimes assume that mantle of power, and fall into the idea that they know better, that they are the healers, and that they stand above their patients.

TD: How do your “Blue Pajamas” paintings, relate to all this?

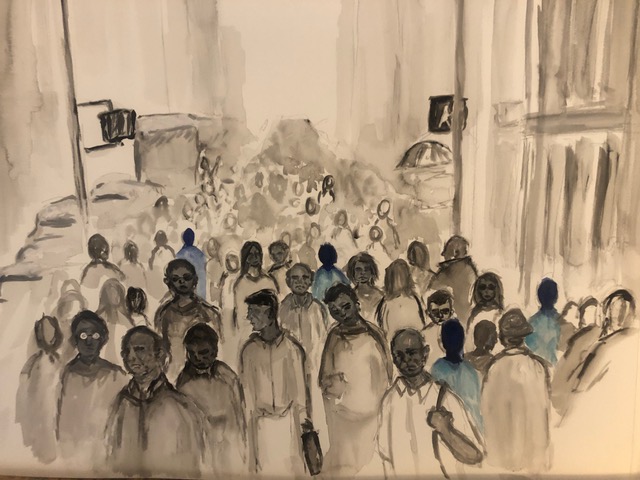

RW: Patients wear blue pajamas that are always too big, too small, or too thin. They fall off, making patients feel powerless and helpless, with little sense of identity. Empathizing with the patients, I began wondering what it must be like to be locked in the hospital, away from home and their families. They don’t even have the clothing they came in with, the last marker of their identity.

Patients are already experiencing a psychological crisis and, to top it off, are now physically uncomfortable. I found the whole thing strange and poignant. I started leaving the hospital and, on my way home, looking around, saying ok, now I am no longer in this locked unit. I am back out in the world. Looking and seeing the outer world was not any saner. Any one of us can be a future or past patient.

We are all emotionally and mentally vulnerable because the human condition is vulnerable. Our physical and mental conditions are susceptible to stress and breakdown. We all, at times, face despair, rage, and even madness. But just some of us are forced into lockdown? Who are the crazy ones? The ones with the pajamas, the designated ones? At one point, I was fantasizing that people around me were wearing blue pajamas, that even I was wearing them, so I got a pair just to see what it felt like.

TD: People often say that when you work somewhere, you become part of the environment, and the question I’d ask in your case is — did you see yourself more relating to the patients or the administration and the doctors?

RW: I’ve asked myself this question, and, at times, I definitely felt like I was identifying more with patients. And it was scary to identify that way. It made me think that at any moment, I could be one of the patients here, locked up, getting in touch with the tenuousness of mental health. I felt that it would be more appropriate for me to wear blue pajamas than a doctor’s white coat.

TD: What are you doing with “Blue Pajamas”? Why did you choose paint as your medium?

RW: The image that struck me most — these pajamas and people walking around — took hold of me. People alone, or even alone in a crowd, isolated, amid the city. I wanted to render the images I saw in my mind, so I started painting these images.

TD: There’s a fine line between what is normal and abnormal.

RW: Working in the hospital got me thinking about the spectrum of illness and health. You might not even realize it when you get to a certain space. Some can be on the spectrum, and they make it work somehow. They function, can have a job, and deal with life within the framework of their mental illness.

I did identify with the patients I got to know while working there. Mental health is so complex. There has been a lot of work done to destigmatize mental illness, but there is much more to do to recognize how fluid the spectrum of mental illness can be. People can be acutely mentally ill like someone is acutely physically ill, say with cancer. Somehow mental illness has an otherworldly quality, like when we see people talking to themselves or know they have hallucinations or other psychotic features. It’s so alien to us that there is immediate stigmatization.

I myself have gone to therapy. Therapists and people in therapeutic roles can offer a lot — usually just by listening, attending carefully to a person’s nonverbal cues, and seeing that person through a caring, nonjudgmental lens. Undivided attention is a wonderful gift. But I also think the power dynamic in mental health professions can be subtle and problematic. Good therapists do what they can to help patients empower themselves by feeling their own strength and health. A good therapist is humbled by how deep and complex each individual is.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Rachel Wyman is a movement-based multidisciplinary artist, and a Licensed Creative Arts Therapist in the state of New York. She was born and raised in Walla Walla, Washington. Visit daisybuckwheat.com