New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

New York, Time Machine

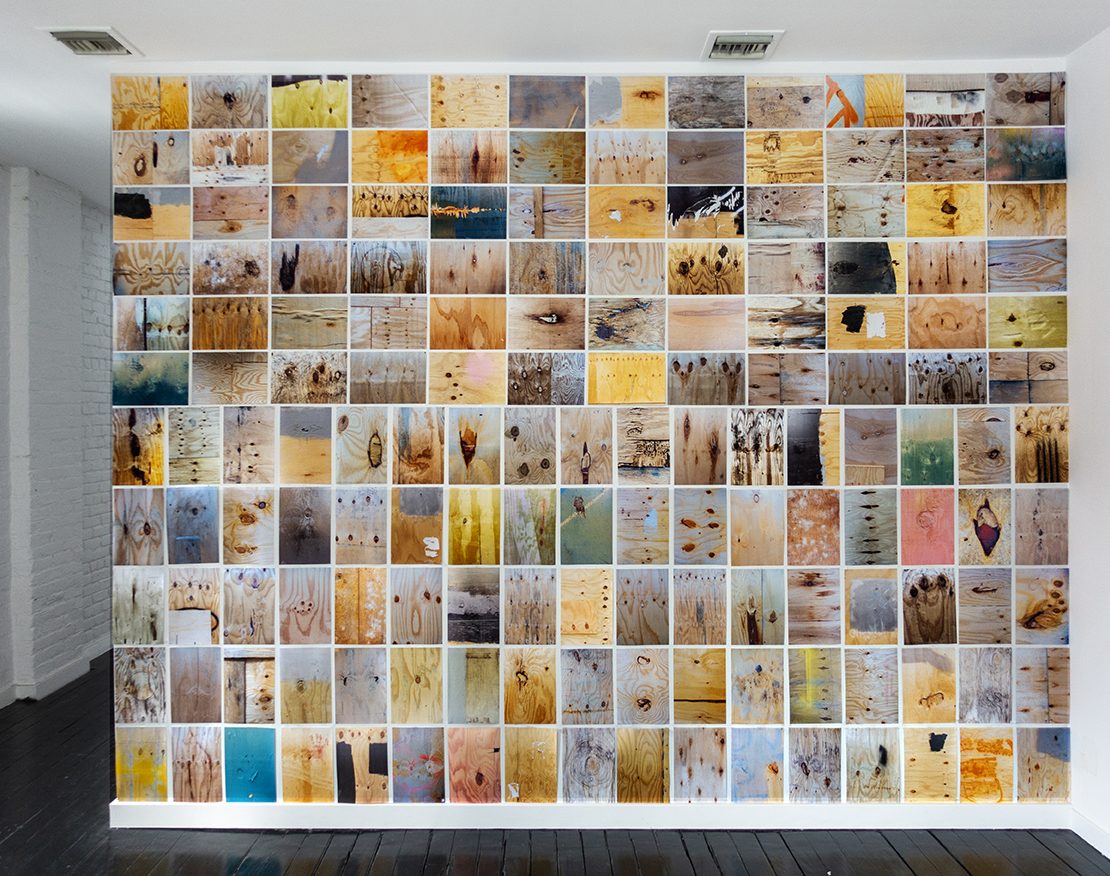

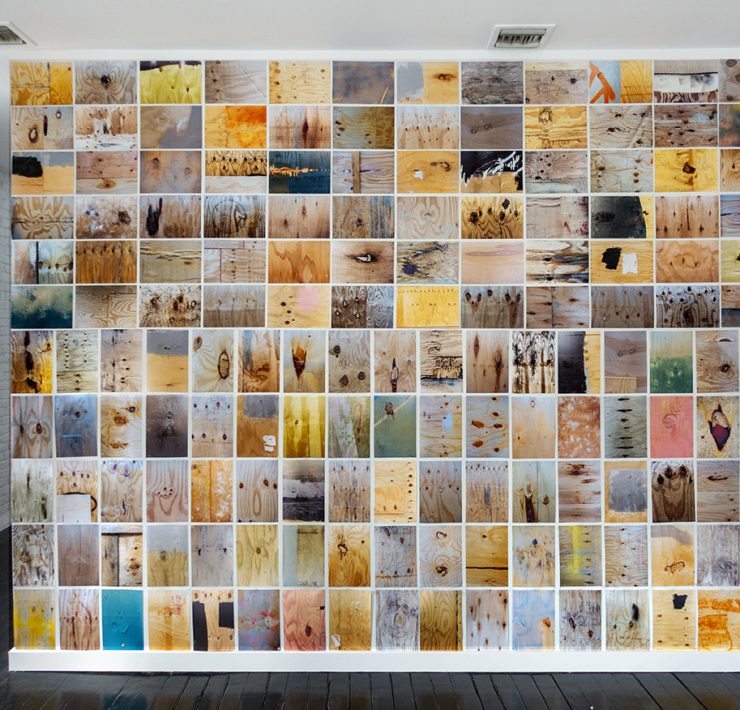

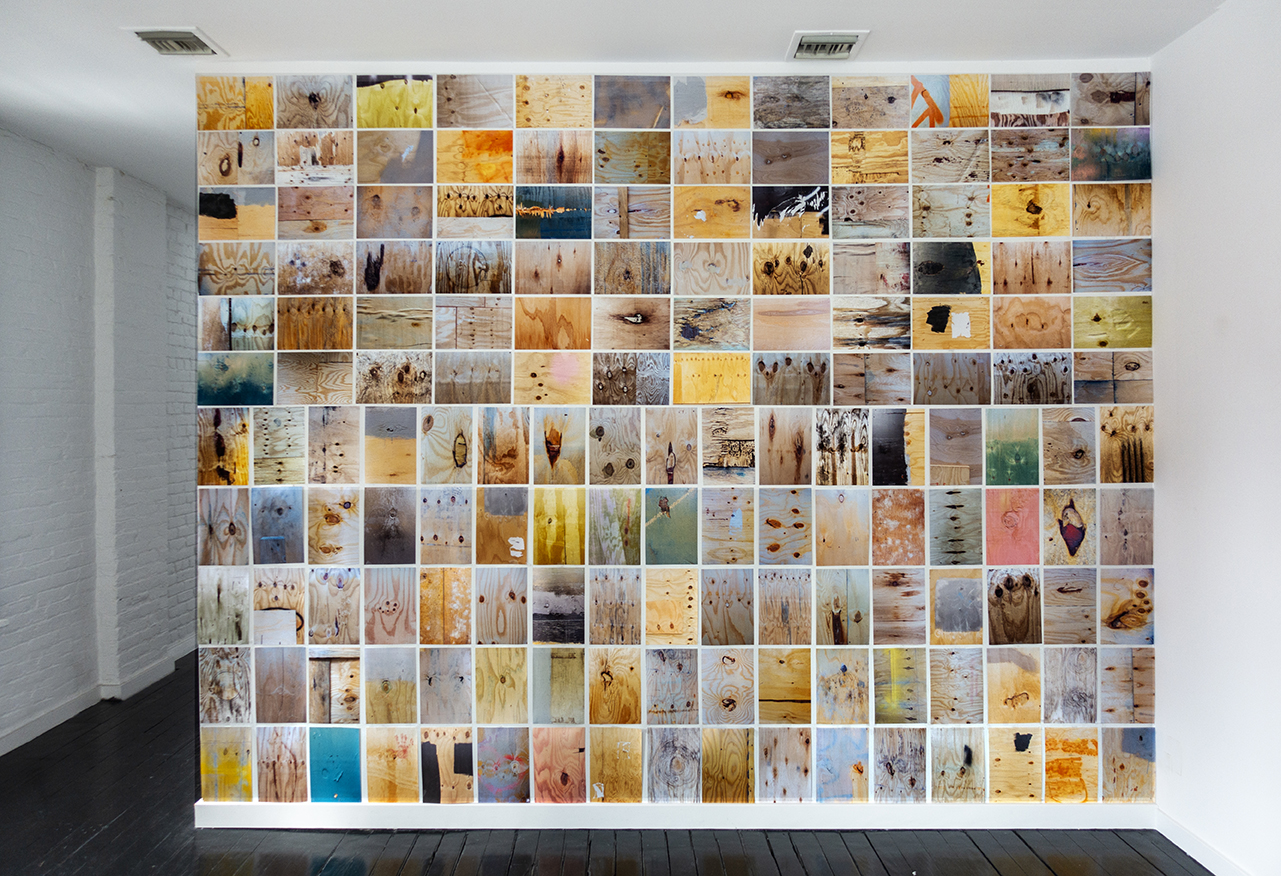

Abby Robinson’s Lamentation, photographs featuring plywood, chronicles a period of protest and civil unrest in a Soho you won’t find on any walking tour.

Abby Robinson is sitting at her vintage card table. We’re sipping mint tea and talking about her upcoming trip to Madagascar, which will be her first time overseas since the pandemic started two years ago. For someone known for venturing across the world to make pictures and guest lecture, being stuck in New York has been quite the restraint.

Since the late 1970s, Abby has been teaching photography at the School of Visual Arts and traveling between engagements. Whether it’s photographing zillions of Pambayas in Sri Lanka (“some of them were quite ingenious”) or channeling her inner detective to document photo studios in Asia (“the color was ferocious”), Abby taps into accidents and surprises to create series that illuminate more universal truths about our state of being. The photo studios, for one, became relics in real-time, as the digital age replaced painted backdrops with pixels. Lamentation, an expansive grid of plywood photos, serves as a record of New York City during the Black Lives Matter movement.

Abby created this limited series in response to the world shutting down in the heat of the pandemic and stores boarding up. New York-bound, she got out of the house to get a routine going, and it turned out that the shops in Soho, right near her apartment, were covering their windows with plywood. This material became her focus. Abby blends color and detail in ways that she’d never really done before in New York City, and she checked in with The Daring to talk about the new tone, the early detective work that influences her, and the importance of the unpretty in her life.

The Daring: One of your first photography jobs was for a detective. Can you talk about your sleuthing days and how they influence the flavor of this series?

Abby Robinson: Oh yeah. Well, it’s had a remarkable effect. I used to read a lot of detective novels. I mean, that was just the thing I did — and I particularly liked the noir ones. And I knew a lot of lawyers then, for some reason. And, I don’t know, they needed detectives to do things. So one of them said, “We need some pictures. Do you want to do this?” And I said, “Sure.”

And then I had a rather remarkable fantasy, of course, that Humphrey Bogart would come to the door in his coat and sweep me off my feet. And I mean, it was quite extensive. And when I got to the door…kind of not! Did you ever see Midnight Cowboy? He looked more like Ratso Rizzo.

His name was Ralph. And so the first case we went on was an adultery case (and I was on the wrong side, as it turned out). What you had to prove back then was opportunity and inclination, and that was it. So we had to be on the roof of The Ansonia Hotel and supposedly get pictures.

TD: How did you get roof access?

AR: Through The Continental Baths. Oh, which is the gay bathhouse where Bette Midler got her start, as it turns out. Anyway, we had to go down through the baths first and then go up. I guess Ralph made some deal with the guys down there.

TD: Amazing.

AR: He also told me, “Don’t look too conspicuous.” I had this humongous lens, so I just wrapped it in a garbage bag. I looked like a sniper in shorts, but anyway. And with us doing this was his operative, Lou. And Lou was, I don’t know, 300 something pounds. It was July or something, it was hot. And there was, I think, one chair. Lou would sit in the chair, and it would just sink into the top.

Apparently, the night before I arrived, a lot of hot and heavy sex stuff was going on. The minute I got there, there was nothing. As it turned out, we never saw anything. I don’t even think that they were trying to avoid us. I think they were just lucky. We did this for five nights. And you get bored. So you just start looking around at other people’s stuff, which was amusing.

TD: And what were some of the more conceptual photos you did for Ralph?

AR: I had to go to the meat department of a grocery store in Harlem. So I had to photograph a meat aisle and, again, not look conspicuous. I said, “Don’t look conspicuous? They’re going to see me from 96th Street. Little white honky coming up there.” And it was ridiculous. Another was an apartment in the Bronx, where, allegedly, someone had hidden guns on top of a six-foot armoire. And I was supposed to show via the photographs that even a six-foot person could not see on top of the armoire.

I mean, I had to take pictures of this armoire with a step stool, from the first step to the third step, and from three feet to nine feet away. There was a guy armed with a tape measure, and there was this ridiculous armoire and an empty pizza box on the floor. Allegedly, this person could not see the guns.

TD: So you’re building a case with this evidence.

AR: Yeah. You were always looking for clues and making some sort of narrative. And I didn’t realize quite how much it affected me until later. But yeah, I loved doing it. I thought it was funny, which always helps with my projects, and … weirdly conceptual. And I did actually write a book about it that got published. It’s called The Dick and Jane, and it’s probably 99 cents on Amazon. Anyway, somebody asked me if it was autobiographical. And I said no because all the sex was good.

TD: And speaking of good, you’ve said that your projects usually start because you think something’s goofy or funny. What happened with the humor in the summer of 2020?

AR: That wasn’t funny. I mean, it was hard to be funny then. No, Lamentation is slightly off ground, an offshoot. On the other hand, it is not surprising to me that I found some weird detail to use as a framework for this.

But like everything, there’s this texture, and how it gets beaten up is always pretty intriguing, and it’s in the details. What detail tells you can help you tell the story. All my projects usually start either as a mistake or a goof. I’m a very bad role model.

TD: So you’re following inertia, in a way. When a goof happens, how do you react?

AR: Well, I don’t necessarily know in the beginning. It’s not like, oh, this is it. Anything that I start to do seriously never happens. Like at a Fulbright, I wrote actually a very well-written proposal and I got there, and I was like, I don’t want to do this. This is really boring. The world doesn’t need these pictures. I’m not sure the world needed the other pictures [I made] either, but they didn’t, you know, need more pictures of sacred sites. And so I started doing weird interiors and old photo studios instead of sacred sites.

TD: You could argue that they were sacred to somebody.

AR: Oh yes, we can. And the other thing in all of it — and I suppose I never put it this way before since I was always working for the defense — they’re sort of underdog projects. I always think beautiful people can take care of themselves. They don’t need any help. They’re fine. It’s people who aren’t who need help to be recognized at all. And so I tend to pick things that are kind of in that underdog arena. I try to make them look, to me, beautiful.

TD: And you made the plywood look exquisite, even though it represents a volatile time in New York City. Everybody was boarding up their shops because they were scared of rioting. How did these pictures come to be?

AR: It was the Black Lives Matter demonstrations. And a lot of them happened in Soho. So it was nearby. That whole series was … I mean, they’re all surprises, but this was a different kind of surprise. A lot of things happened. One, I walked around a lot just to get out of the house, and two, I wasn’t taking public transportation, so I was walking everywhere. And I have done this before. I pick something to look for.

And so, here I was in Manhattan, aimless enough, and I think the plywood gave me something to do and to look for. And along whatever route I was going, there was stuff to look at. I mean, I didn’t expect it to be anything. I just started photographing it, and then I started putting them up [on the wall]. And then I did get caught up in how much of it looks the same and how much it looks different. There are many different kinds, and there is also a remarkable number of similar kinds. And there were a lot of them.

TD: Any revelations?

AR: Three things happened. One, I have not shot in New York for a really long time, so I was surprised I could make work here again. Two, I thought of New York as colorless, which this [series] is not. And three, I usually don’t make site-specific or time-specific work, and I’m not going to add to this. I mean, I see plywood now, and I don’t bother shooting it. These are from that time.

TD: How does it feel to have birthed something that’s now complete?

AR: Well, it was psychologically quite helpful that I could actually make something. And that doesn’t matter to the viewer, but for me, yeah. One of the things about my career is I became a photographer because I was sick. And one of the reasons is a comment I got that even I could raise a camera in bed and shoot. I always love the idea that you can feel like shit and make something. So [Lamentation] is kind of another one of those. And so the muse descends when it descends, which in some ways it’s excellent or sometimes torture.

TD: Overall, Lamentation feels very soothing. I think it’s your vantage point, you’re looking straight on. And you’re zoomed in, so you’re eliminating the chaos.

AR: Yeah. And actually, what’s interesting now that I think about it too, during the pandemic, which is scary, [Lamenation] is pretty quiet. And the textures vary. I mean, some of them are sort of serene, and some of them are not. But with Blursday, once Lamentation was over, I went into chaos again.

Although in terms of using material, both projects are very material determined. How much can you do with very few variables? And so, sticking to plywood or sticking to plastic. I mean … like a magician, how many bunnies can you pull out of the same hat? And that kind of fascinates me.

TD: They are really powerful as a grid.

AR: Yeah. I mean, there are some that don’t look too bad by themselves. But yes, it’s the whole thing. And the patterns were really beautiful. And I guess what was interesting to me is how much some of them could start to resemble little paintings.

And it also was intriguing that if you cranked up the color they would change. Usually, I don’t make up colors. And I’m always accused of it, but I don’t. I guess I don’t even think about it because, for me, it would look too fake. And the other thing is, I can’t make things up. I’m not a good fabulist. That’s another sort of boundary. I think the world is weird enough that all I have to do is extract things.

When you came in and commented about the detective, that is an entry point to a lot of my work. All my work, everything is kind of a surprise. And I am charmed, I have to say, that I can still surprise myself. When I went out with Ralph on detective work, I certainly did not think it would be life-changing. And Ralph would certainly roll his eyes around his head.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Abby Robinson lives and works in NYC. She teaches at the School of Visual Arts in the BFA Photography & Video and Graphic Design & Advertising Departments. Visit abbyrobinson.com.