There Is No End to Gloria Deitcher

There Is No End to Gloria Deitcher

There Is No End to Gloria Deitcher

“I have always felt desired, appreciated, and excited by the male gaze,” says Gloria Deitcher, a feminist multimedia artist. She suggests we reverse the psycho-sexual reality of a woman artist and her subject matter. “I want to have my muse…in my seventies.” And why should there be any difference between a male and a female gaze?

Perhaps it’s because I’ve recently found myself in the aging vortex that this is top of mind, but the chatter about women reaching a certain age — about the ghost female — has been going on for generations. Who is she? Where did she go? And was she ever here?

After 40, women sense an invisibility, perhaps at times encountering reflections of themselves from the corners of their social and cultural periphery. What do the outer realms of our universe mirror back at these female phantoms?

Our consumer culture, obsessed with preserving youth, conducting plastic surgery on eighteen-year-old girls, and hyper-focusing on perfection, disregards the aging, treating, mostly women, as junk for grabs. But no one is grabbing.

Women reach an age that no longer invites hungry glances from the male gaze — a gaze many women might have considered misogynistic, a nuisance, even a threat at an earlier stage in life that has now become something of a craving — even desire. Throughout history, the male gaze determined which women were desirable, often objectifying and categorizing who was beautiful or sexy, who was a porn kitten, and who was mother material. This characterization forced foundational limitations on a woman and what may be her most prized virtue — particularly after her youth fades, which is the root of her identity.

Perhaps at this stage in her life, she is recognized for her intellect, personal success, and opinions. Colette once wrote, “that lightheartedness which comes to a woman when the peril of men has left her.” She understood the question of the ghost woman who must find other ways to define herself, outside of what we know as the male gaze. But what a predicament a woman might find herself in if she wants the pleasure of both worlds.

Alice Steinbach wrote in The Baltimore Sun that “Gloria Steinem once suggested that Marilyn Monroe was a female impersonator; that all women are female impersonators. What we are impersonating, in this context, is the male vision of what a woman is or ought to be. But the vision of what women ought to be stops somewhere around the age of 50. The male gaze has no vision beyond that. And so women become ‘invisible.’”

Of course, not everyone feels this way, and not everyone fits into the cliches I just projected on the page when describing women. But stay with me for a moment. Does it actually matter at what age a girl or a woman begins or ends feeling invisible? Perhaps not. What matters is how the world sees her, how she is projected outwardly to her “audience,” eventually influencing an image of herself — there — far in the distance, that might not even satisfy her own expectations of self. Perhaps she will be forced to abide by a fixed trajectory, identified as the inherited lot of her female sentence.

It’s a cruel process — becoming invisible in a society that amplifies aging in the backdrop of time, using technological advancement to simulate the youthful “you.”

“I never experienced a more intimate and intense experience than the one I shared with a brilliant and very talented musician during the pandemic,” says Gloria. Our platonic and artistic friendship evolved during these two and a half years, and I became very prolific, making paintings large and small, as well as several videos. Now I am shattered with grief because he died from a massive heart attack several weeks ago. We connected online, texting, long phone conversations, sharing music and visual images.”

Gloria’s work has always been female-driven, and she was quite a feminist in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. In our interview, I wanted to narrow in on the femininity fermenting in her art and her search for what femininity means — particularly within the confines of the roles women are assigned to satisfy, societal expectations, roles forced on by familial pressures and obligations, often using systemic guilt.

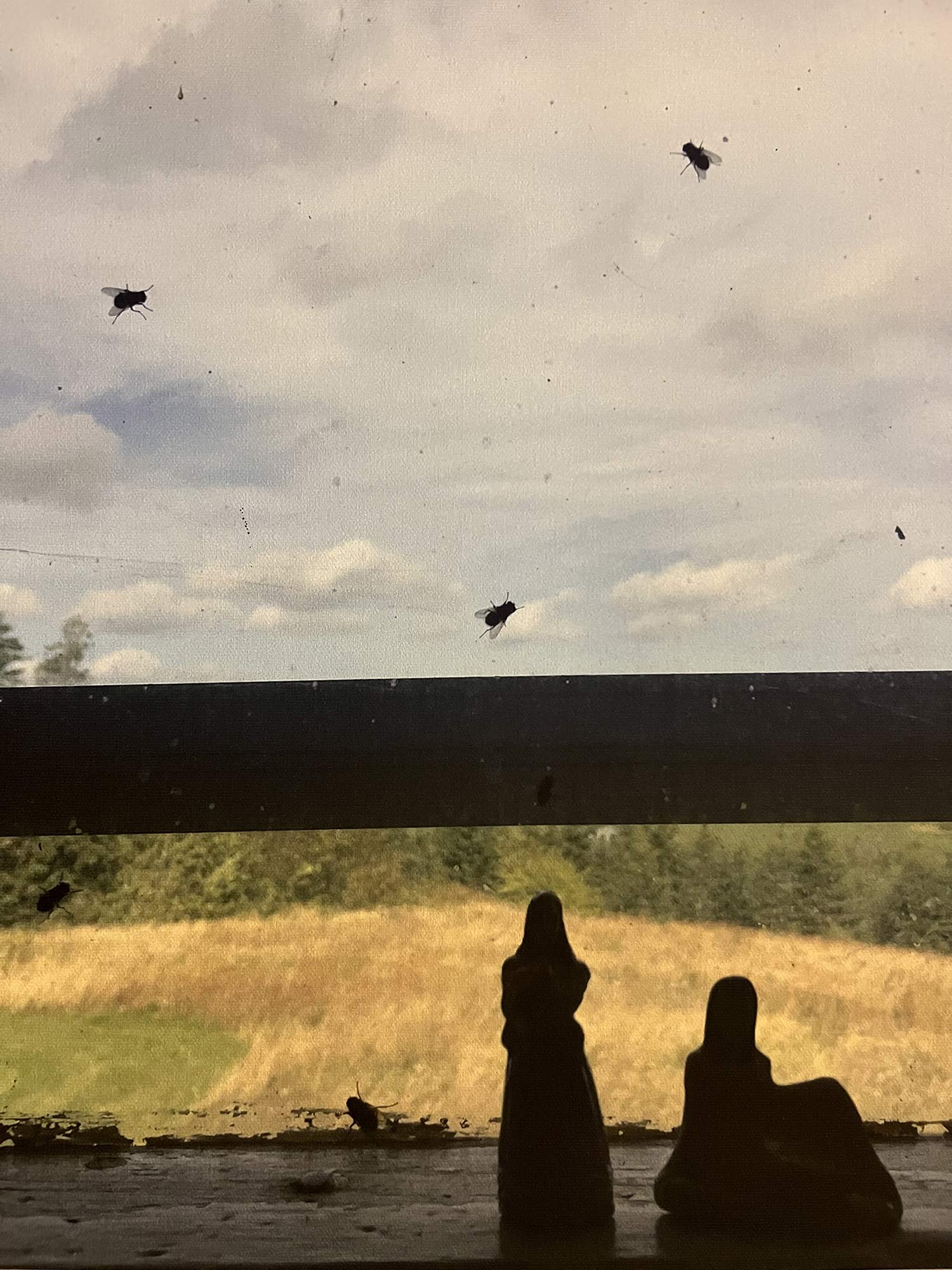

In her earlier video work, Gloria employs some of the roles women play, placing the mother/daughter relation at the epicenter. She creates a small series that captures her family’s essence while shining light on the layering of identity, the artistic and female self. But in making this work, she often had to fend off a male-dominant art world, particularly the New York City art gallery scene and the men running it.

A 2018 article in The Guardian states that just 12% of the artists in U.S. museums were women — and figures from the UK tell a similar tale. In 2019, The Smithsonian Magazine published an article revealing a comprehensive study that 85% of artists featured in permanent collections are white — 87% are men.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts published a survey that only 13.7% of living artists represented by galleries in Europe and North America are women. The study’s co-author, Marina Gertsberg, notes that “galleries may discriminate for the same reason the broader market does: they’re skeptical about emerging female artists’ likelihood of future success. Dealers may be concerned that a woman will take time off to have children and raise a family — thereby making her career trajectory and prospective output less reliable than that of a man.”

Gloria encountered exactly that kind of pushback when starting out. She was a new mom, in her thirties, when she made What Price This Sweet Paradise and Coming Down the Home Stretch Part I and II. The latter videos were taboo, going against the normative, and captivating. She used the mother/daughter relationship to delve into the psychological metamorphosis of raising and being raised female. While transitioning from a promising career in the New York art scene into motherhood, Gloria had to put her career on hold, compromising her success. She eventually takes back the reign over her talent by returning to the art world — only now as a multi-layered, more complex female artist.

Coming Down the Home Stretch, Part I

Gloria Deitcher: My last exhibition was in Tribeca during the height of Covid. I was at a bar with a couple of friends when I got a call from Martin Schoeller, a staff photographer for The New Yorker. He asked if I wanted to be in this group show. I had done these digital photographs on canvas four years earlier relating to this dystopian feeling when Trump came to office. I put five of them in the show. I mean, Martin and Philip-Lorca diCorcia and other filmmakers were there — I suddenly felt validated. It was such a wonderful feeling to be visible again.

The Daring: Tell me a little about your experience as an artist in the ’70s and ’80s.

GD: Mid-seventies, we were doing real-to-reel video. At that time, videos were in their infancy, and people weren’t making them. I befriended this fellow who did a lot of video work and knew Nam June Paik, a Korean American artist who many considered the founder of video art. Through this contact, I made five or six master tapes and grew an audience on cable television. I did all this out of the University of Bridgeport — I was in the art residency there. I also got into this amazing show curated by Sam Hunter.

But the isolation I experienced as an artist, having a young child — what was the trajectory for me? I decided to cut myself off from it all, although I still continued to paint and present at shows.

TD: What made you feel like you needed to cut yourself off from the New York City art scene?

GD: Many artists, especially women, were giving up because they’d say, what is the point if our names are not in Pace or any big-name galleries? Plus, the gallery system was not great. It’s still not great, but it’s getting better.

I almost had immediate fame because of art dealer Leo Castelli, who told me he loved my work and asked what I wanted to do with it. At the time, I didn’t know what to say. I had no time for a plan. I was busy being a mom in a new city. Leo asked if I wanted to leave my videos with him and said Susan Brundage would look at my work — she was big in the video art scene. I waited months for a response. Then I did something silly — I pulled the work out.

A lot of my content was feminist based, about being a woman and the experiences of a mother. Taking the personal and putting it out there, using the most contemporary medium, which was video. I brought my daughter to the University of Bridgeport, where I interacted with her on stage while working with the technicians. So she became part of my project, and when I presented the video, people didn’t like it.

I was combining a feminist approach with video and audience —to me, this was universality. Ahead of the curve — I made a narrative of my life experience. This was the role of a multi-tasker, juggling the multi-faceted identity of being a woman and a mother. It was also around the time, during my pregnancy, that I had a terrible tragedy in my family. My brother killed himself —something I openly talk about in What Price This Sweet Paradise.

What Price This Sweet Paradise?

TD: For me, the way you layered emotion created a sort of madness, and the background noise served as the typical noise women often hear about how they should be, what they need to do, how to obey, and who to follow. It can be detrimental to our well-being and is almost impossible to navigate, yet women somehow do it. The way you structured the video, it felt like you were interviewing your daughter, which I thought was powerful.

GD: I went from photographing birthing and silk screening to making videos. When I showed my project at Rutgers, the reaction from one of the women was that I was exploiting my child. Another artist had taken nude photos of her child and was also criticized. For some, the personal and the political don’t work well, but to me, they interconnect.

TD: In your other videos, you are sitting with your mother in what looks and feels like an interview. Even though there wasn’t much action, your interaction with her was immensely impactful — how you insisted on truth — I feel like you achieved it. Can you speak a bit more about your intention?

GD: My mom went through a lot, particularly with my father, who was a real Romeo. She also came from a traditional Jewish family and was creatively neglected. So, in some respects, she was threatened by me. She never came to my shows or supported my work. She emphasized who I married, my children, and how she saw me as a mother.

Coming Down The Home Stretch, Part II

TD: This idea of how female roles pass down from generation to generation. Anything domestic seems within bounds and anything creative — well, that’s a different story.

GD: I think for women artists, it’s just always about being marginalized, especially for Black female artists. Then we also have to deal with everything else in our personal lives.

Every time I attempted to push myself further, it backfired emotionally. One of the worst feelings in my life was after the Art Bank of Canada purchased a series I did on the Montreal metro for their collection in Ottawa. My brother then jumped in front of the very subway on which I did the series. We were very close, and I know he didn’t have a history of mental illness. Still, he had a breakdown while attending the University of Montreal during the Separatist movement, and I think he was not getting proper help. A suicide is a suicide — but for years, I was riddled with guilt thinking I caused his death.

TD: Women’s voices seem louder now, and they have social media to help them fight the fight. What has changed in the art world? Has it evolved from a woman’s standpoint?

GD: It has changed a lot. I think women artists are much more confident. In terms of marketability — I think if they go to the right schools, get shows, and push really hard, they’ll make it. But once they have children — they might still have a difficult trajectory.

TD: Why is that so?

GD: It’s part of the gallery system. If you are a gallery owner, you are investing a huge amount of money in marketing the artist, and women’s art just doesn’t buy the same way as men’s. Lack of visibility, perhaps. I recently went to the Basel Art Fair and spoke to a famous male gallery owner who said women don’t bring that much money. There’s this idea about a woman artist potentially having a child —it’s stigmatized.

I strongly felt a market change as soon as I had a baby. I remember going to the gallery pregnant, and I was pushed and shoved, treated like I was invisible. It takes tremendous tenacity to get through that psychologically. I mean, you are already losing sleep, your body is going through hormonal changes, you no longer feel like a sexual object, so where does one fit?

TD: Can you talk about no longer being a sexual object once you are a mother?

GD: I adored my daughter and husband. There were also societal pressures. As a creative person, I felt caged. To maintain my creativity, I had to get out. My husband was very supportive and came to every alternative space performance. But you need space in your head to be creative, and you need to float. And you can’t float with a baby. As a woman, you do so much for the family. It takes years to find space for yourself again, which is a long time to be out of the market. That’s when you become invisible. You always have to be out there. It’s like that in every profession — for women, I mean.

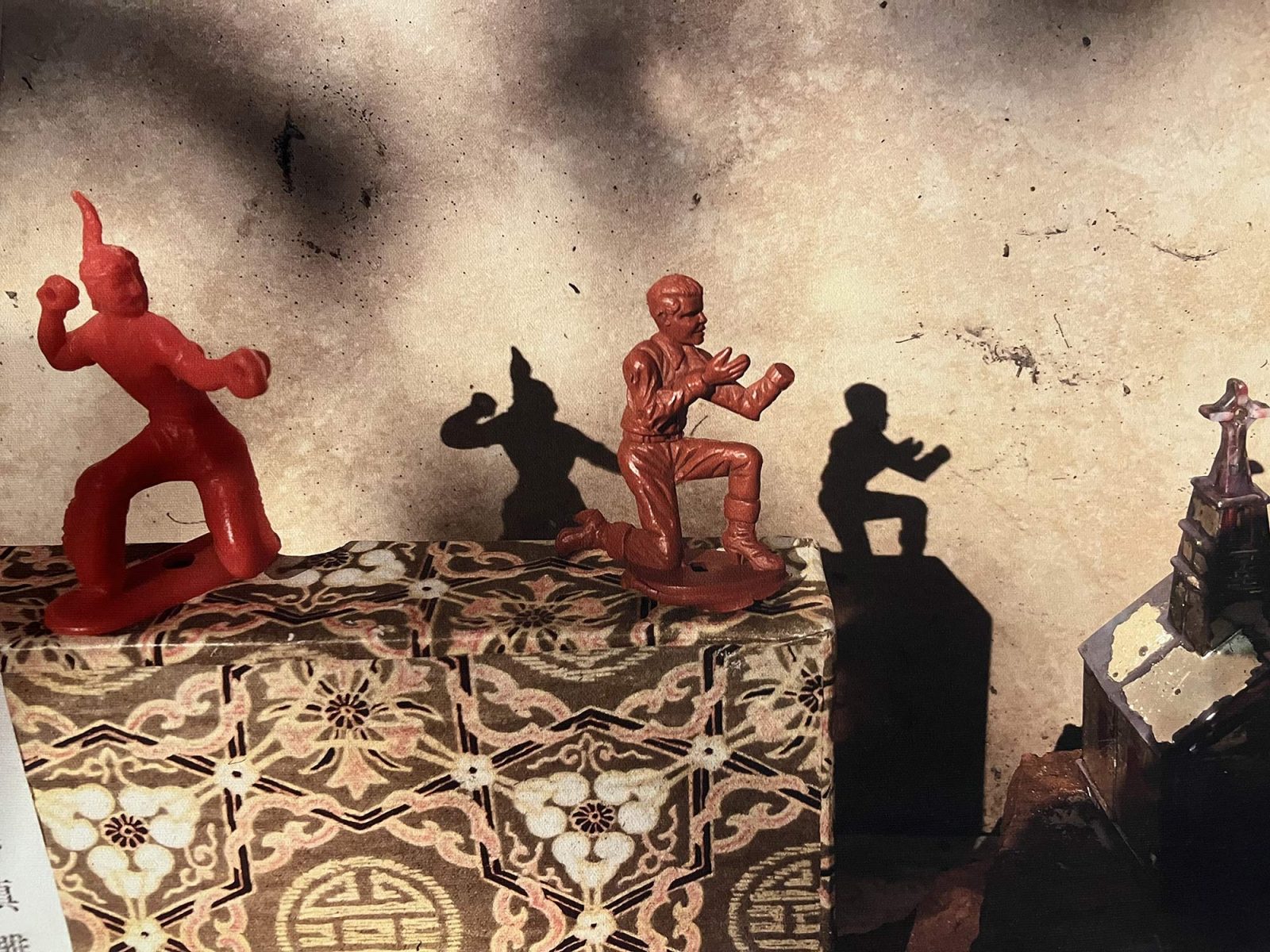

TD: Going back to the male gaze, for centuries, artists and writers used women as subjects and objects — what are your thoughts on the subject — do you feel like those roles might have shifted?

GD: During the pandemic, I found myself sexually attracted to my new friend, and it was a mutually platonic but intimate relationship. So I just let it happen — I was going to use him as my muse. Suddenly, I was the gazer. It was wonderful and empowering. I never produced so much work. And I realized that I was doing something men have been doing for centuries.

TD: It’s interesting to see such transition in women. A woman in her youth might resent being objectified or seen as a sexual object. Then, later in life, she might desire that feeling from men. Any thoughts on this shift?

GD: I see it all as theater. Whoever is gazing at you is actively in the performative stage, and you fill that space and perform as well. Now it is no longer binary. The lines are blurry, which I think will be good for women. Maybe I feel this way because I have a gay daughter. Even in the gay community, you still have power roles, and it parallels.

TD: What are you working on now?

GD: I am painting a Humpty Dumpty series based on my muse. It’s an interesting area to explore — the psycho-sexual reality of a woman artist and her subject matter, and I want to explore it in more detail. I also want to paint birds and women flying and falling — connected to Roe vs. Wade, which has seriously impacted me. Representing women is important, as there will be a lot of repression and consequences for us due to this nightmare.

TD: Any thoughts on Roe vs. Wade?

GD: It’s very upsetting, especially because I have daughters and a granddaughter. I had no idea I would have to deal with this again in my old age. Of course, it is socio-economic. Many women won’t be able to get proper care and will have to cross state lines. It’s like going back to hangers again. But if we fight the behavior, I feel we can change things.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Gloria Deitcher was born in Montreal, Canada, where she studied printmaking and painting. She received a Canada Council Arts Grant and has exhibited prints extensively across Canada and Europe. Visit gloriadeitcher.com.