Welcome to the second installment of our brand new series, Spotlight, a monthly interview with a leading light from the world of visual storytelling. Every first Thursday, we’ll publish a new Q&A here on The Daring. Today, our editor Ioana Friedman meets with documentary photographer and recent School of Visual Arts graduate Akshat Bagla.

The New York-based photographer journeyed back to the land where he grew up and where his family still lives, aiming to further understand Kolkata’s history and document the culturally layered metropolis.

Within seconds of joining a Zoom call with Akshat Bagla, I’m feeling more relaxed. The 22-year-old photographer emanates a confident and calm air, speaking in a soft Indian timbre about the goings-on of his day and upcoming graduation from School of Visual Arts. For someone who’s moved across the world to study photography — and is now in the process of figuring out how to stay in the United States to pursue a career in the industry — the unknown hasn’t knocked him off his game. If anything, as I learn during our conversation, it’s helped focus him.

Akshat jumped into documentary photography at thirteen and things changed for him almost immediately. He credits an older cousin for showing him how to use a camera. At a family gathering, while everyone feasted on Chinese food, the two bonded over photographing details around the restaurant. “I thank my cousin, he’s the reason I’m here,” Akshat says, and describes filling up the memory card right there, in two hours. His eyes widen and his tone lifts, reliving the delight of the moment it gelled that photography “was it.” Indeed, he spent his high-school years photographing everything he could — his friends in nature, street scenes.

That Akshat ended up studying photography in New York City still thrills him. He is the only child of business owners, raw paper distributors, who’d diligently trained him to take over the business after completing his studies. While Akshat’s parents set their expectations early on, it never stopped them from supporting his interest in photography (his dad, Ashish, bought him a camera) and introducing him to classic movies and songs. As the story goes, when time came to make decisions for the future, Akshat worked up the courage to tell his parents that he wanted to go into photography and video. “I just knew the family business wasn’t for me,” he recalls. So what happened? Through the power of persuasion (and patient conversations about his photos) Akshat dissolved his parents’ initial skepticism. Not only that, they recognized his talent and let him pursue further studies.

Four years later, his creative practice is maturing every day and already spans a dynamic range. He’s made portraits, has documented the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in New York, and detailed places he has traveled to, like Bali and Jaipur. What unites all his work is an understanding of the power of images, their ability to communicate emotion in a split second, and their capacity for presenting us with the nuanced nature of things. Keeping with tradition, Akshat’s parents had been protective of him as a kid and didn’t let him explore Kolkata, especially alone. He came to know his birthplace as a young adult by photographing its nooks and subtleties — and his return is at the heart of our discussion.

The Daring: First off, you mentioned a turning point when you fell in love with photography more than you could’ve imagined. What pulled you in?

Akshat Bagla: Yeah, so I’ll tell you what got to me. When I came home, I put everything on the computer, and I saw the images. I was reliving the whole moment. I was looking at something I experienced but in the form of a photo, which I could cherish for the longest time. What got to me more than the camera and the medium itself is the whole idea of capturing a moment for eternity, you know?

TD: Sounds visceral…how do you think reliving moments changed you?

AB: For sure, I will say it opened me up as a person. Photography made me more outgoing and able to talk to anyone, anywhere. I love talking to strangers, being out in the world, walking around, and experiencing new things, which helps with street photography because you never know what might come your way.

And then, when I moved to New York to go to SVA, I learned how to look around and automatically frame images in my head. I saw things from a whole new perspective. The experience of coming to America and starting photography and opening up has benefited me more than I could have ever imagined.

TD: Wow. That’s incredible. What did you learn about yourself as your eye and creative practice started to develop?

AB: That I’m a true Gemini because I have polar opposites. I’m either extroverted, or I don’t want to meet anyone…and I’m trying to find a middle ground right now where I can manage both.

Initially, when I moved to New York, I was a social animal, going out and documenting protests and election stuff. Then I realized I need downtime to recollect because that work can be overwhelming. You meet thousands of people going towards one powerful demonstration, one powerful system. It gets to be so much at the end of the day, when you come back home, sit down, and think about it. A lot of emotion builds up over the whole day because you’re snapping, snapping, snapping in these fast-paced moments where there’s no space to recollect.

TD: And how do you think about building rapport with the people you photograph, even at protests?

AB: Well, you got to know how to talk to people…I feel like I have sharpened my skill in that. Let’s say I’m approaching someone because I like their style of fashion. That’s the first thing I’m going to say before I do anything. Before I ask them for a photo, I will talk to them about their fashion or something about them that would engage them in conversation. If I do that, then it’s easier to document what they’re about. I’m trying to tell their story at the end of the day.

There are times when I talk with people and ask them to stand in a particular way, and there are also times where it’s a spontaneous moment, so I take the picture, and then I go and talk with them. I show everyone the photographs and always attempt to get their contact information to send them the photos after I edit them. They always reply, too.

TD: Oh, that’s lovely. What was it like returning to Kolkata and making pictures there?

AB: I went back exactly one year ago when the pandemic started in March. I’m not a child anymore, so my parents were okay with me going out on my own. Every day, I woke up at 8 AM to go out and shoot. I explored so many areas, and I talked to more people than I ever did in the sixteen years of living there before. One benefit of making work in India is that I know the local language.

So, when I say I saw Kolkata in new ways, I mean both literally and metaphorically. Literally, because I experienced places in Kolkata that I hadn’t before…and metaphorically, in the sense that I understood so much more. Just meeting new people and learning about their experiences opened me up wholly to the aspects of Kolkata I wanted to show through photos. It gave me the exact direction that I wanted to head into. You know, when you Google Kolkata, you see the Victoria Memorial, and you see the Howrah Bridge, which is not what I want to show. Everyone knows about the Victoria Memorial or the Howrah Bridge, but not about the people who run it. I want to show the people. The true ethnicity of Kolkata lies within the people and these small areas, these small, congested areas.

TD: When you say you want to show the real Kolkata, not the tourism version, what’s the difference for you?

AB: Listen, I’ve had this issue since I started to understand the internet and saw how places are shown. I’ve always been an avid traveler, and I research before going somewhere new. Every time I search a spot on Google, I see photographs showing that it’s so beautiful, there’s no crowd, there’s just good, good, good.

But when I get there and see two-hour lines, it’s clear that what’s on Google isn’t the whole truth. It bothers me. I have a genuine issue with it. I want to go to the Taj Mahal and photograph those four-hour lines instead of showing an empty place, because that’s the reality. I’m not saying that the Taj Mahal is not beautiful. Just expect to stand in line for four hours. Don’t go there expecting to walk right in. But that’s how it’s shown in the media, which is where the problem arises for me.

TD: And, speaking of nuance and detail…what surprised you as you were documenting your hometown?

AB: How relaxed people can be. I didn’t think people in Kolkata were so laid back because I didn’t experience much of it when I grew up there. I thought people had this one-track mind of going to work, coming home, and that’s all there was to it. But that’s not the case.

You know, some of the people I photographed are old, some go around in a wheelchair. They have much wisdom to share about what they’ve been through and where they’ll go. They’re just going on with their daily life. Just do not bother them in any way, is what I learned. That’s what photographers sometimes lack, I feel, when it comes to approaching people. Don’t charge at people. Talk with them calmly, be friendly, don’t pressure them into anything. Just make them comfortable.

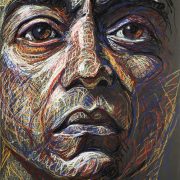

TD: I love that idea of photography being about mutual understanding. There’s a photo I’d love to talk about – it’s of a moment when two gentlemen are shaving their heads. What’s the story behind this image?

AB: Yeah, they are local Bengali people from West Bengal, and they belong to the pandit caste system in India. If you’re part of the community, you maintain a minimal amount of hair on the top of the head, so these gentlemen shave every two months or so…when the hair around the top gets to a certain length. It’s a tradition in India to cut your hair if someone dies in your family or as a sign of appreciation. There are also certain religions in the Indian community that ask you to donate your hair if something good happens in your life.

Before I approached the people, I thought about whether I should disturb them. But I thought this would be a great photo, so I decided to talk with them and see what happens. We spoke for ten minutes or so. They told me they follow a deity in Indian mythology, and they shave by choice as a token of appreciation. It got me thinking, “I’m so averse when people touch my hair, it just bothers me, and these people are willingly sacrificing their hair.”

Initially, they seemed a little disinterested in being photographed. A guy was shaving their hair, and he was not comfortable with pictures, so I cropped him out. They let me photograph them from behind, which also made sense because you can have multiple ways of looking at one thing, and this framing looks very natural and unforced. I’m not in front of them and bothering them. They’re relaxed and letting the whole free flow happen. So this image shows some darkness and the raw style of my work. It shows the everyday reality of their ritual. I tried to understand who they were…and it really made an impact on me. I went back home and thought, “Okay, this is wrong of me to get irritated if someone’s messing with my hair.” I was thinking about it for a week.

TD: You’ve said you go through a process of trying to separate your inherent bias from what’s happening as you make pictures. How do you work through that?

AB: I feel like a large part of it is being out there photographing, and then a large part of it is coming back and sitting down with the photographs.

When I’m photographing, I have my eyes open, and I look at people, and I try to pick up on their emotions. I’m trying to think about that person and put myself in their shoes. I think about what they’re doing, what they’ve been through the whole day, what they’re going to be like tomorrow. I’m also trying to understand what their community stands for.

I’m just trying to separate myself as much as possible. Yes, I’ll have my thought process and opinions, but I’m trying to keep them to myself. I’m trying to approach photographing like if I were to write about it, I’d write about what I talked about with the person, not what I think about them or the topic.

TD: And much of empathizing is being attentive to detail…can you talk about what you look for and tune into?

AB: You can see it on the face. I’ll give you a great example. A few days back, a friend invited me to this party, and there was this one dude…he just looked off. I could tell by his face that something was bothering him, and it turned out he was going through depression and having social anxiety.

I think because…I’ve lived in three different places, and because my family has a business I always got to meet many people. I’ve accumulated sensibility by meeting different kinds of people in all sorts of circumstances. People who’ve just lost a family member…people who got an offer from a company they wanted to work with. I notice how emotions show up on the face.

And I think about these emotions, because to an extent, we feel emotions similarly. I’ll be angry about one thing, another person will be angry about another thing, and the feeling is still the same—anger. When you’re angry, you generally get restless, you get irritated, your face gets tighter and tighter. You’re not laughing anymore. That’s just how I gauge things. I can see when a person is sad and trying to hide their emotions, looking away, not able to talk to me. And because I studied psychology for three years at SVA, I started understanding demeanor even more.

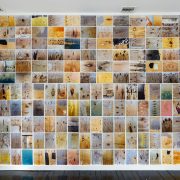

TD: You recently made an intimate portrait of a shop owner in situ. Can you tell us about it?

AB: I really like this image. The man’s making tea and coffee for people, so that’s his store. I ordered a coffee with him, and just started looking at the scene. It was so hot out, and it just made me appreciate this guy so much more for sitting right next to the fire, making tea and coffee for us. I stood there for fifteen minutes, waiting for him to start the stove so that I could capture the fire along with it because I wanted him illuminated. The flame had stopped working, and as he was lighting it back up, it became massive. He was sitting in a corner, and the flames were lighting up the scene perfectly. I showed him my camera, and he just nodded his head to say he was comfortable with it. He didn’t even speak a word and got back to making the coffee.

This photo shows what I see in Kolkata in the most natural way possible. I want people to see the city from the inside and not from a third-person perspective. That makes a huge difference. In this portrait, you can see that it’s so hot, and still, the guy is dedicated to his work. Yes, it’s just a person making tea, and you might not readily think about the whole burner thing, the heat on him, how many times he must have burned his hands. But the emotional connection is what brings his story to life.

To me, the fire in this image is literal and metaphorical. The glow that it’s creating on him, I feel like that’s how people in Kolkata are…with this glow, this energy of fire. They want to conquer everything. The intensity of this image makes me feel warm, calm, and makes me want to achieve things.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Akshat Bagla is a photographer and videographer based in New York City. Specializing in street and travel photography, he also makes studio portraits and conceptual high contrast black and white photography.

In travel photography, Akshat intends to experience everything a country has to offer, to capture the true essence of the culture through immersing himself in the local community and following his passion for the area’s cuisine and culture. When not photographing, he’s a food lover, amateur cook, sports fan, adventurer, and music lover.

Visit akshatbagla.squarespace.com, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Ioana Friedman is an art director and Editor in Chief at The Daring. She’s led digital creative at Estée Lauder Companies and e.l.f. Beauty and has served in a creative capacity at Magnum Photos and powerHouse Books.